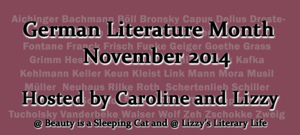

The end of the year is approaching with fast steps. This year I haven’t been so active as a blogger as last year until recently – German Lit Month brought me back to the usual pace – and I have done more blog posts on poetry and translations than the year before; also I did more posts in German and one in Bulgarian too. Book blogging is a dynamic process and the focus of such places will always be subject to small unplanned changes, but I will keep also in the next year my habit to publish reviews of books that were interesting to me.

As you already know when you follow this blog on a regular basis, my taste in books is rather eclectic. I am definitely not a person who is permanently scanning bestseller lists or is jumping in on discussions about books that were – usually for marketing reasons – the “talk of the town”. Therefore I avoided so far reviewing books by Houellebecq or Knausgård; it is difficult to not be influenced by the public discussion that focuses frequently on aspects that have very little to do with the literary quality of the books by such authors but a lot with their public persona and their sometimes very controversial opinions about certain topics. Not that the books by these authors are necessarily bad, but I prefer to read without too much background noise. So I will come also to these authors, but most probably not in the near future.

My blog tries to be diverse, but without quota. But of course my choice is subjective and I am aware of the fact that probably most readers will find many authors/books on this list that are completely unknown to them. If you look for just another blog that is reviewing again and again the same exclusively Anglo-saxon authors, then this might not be the best place for you. If you are eager to discover something new, then you are most welcome.

There are no ads on this blog and this will also not change in the future. There is zero financial interest from my side to keep this blog alive, I do it just for fun. Please don’t send unsolicitated review copies if you are an author or a publisher. In rare cases I might accept a review copy when contacted first but only when I have already an interest in the book. All blog posts contain of course my own – sometimes idiosyncratic – opinion for what it is worth. In general I tend to write reviews on the positive side. When a book disappoints me, I tend to not write a review unless there is a strong reason to do otherwise.

These are the books presently on my “To-be-read” pile; which means they are the one’s that i will most probably read and review within the coming months. But as always with such lists, they are permanently subject to changes, additions, removals. Therefore I (and also the readers of this blog) will take this list as an orientation and not as a strict task on which I have to work one by one.

Chinua Achebe: Things Fall Apart

Jim al-Khalili: The House of Wisdom

Ryunosunke Akutagawa: Kappa

Rabih Alameddine: The Hakawati

Sinan Antoon: The Corpse Washer

Toufic Youssef Aouad: Le Pain

Abhijit Banerjee / Esther Duflo: Poor Economics

Hoda Barakat: Le Royaume de cette terre

Adolfo Bioy Casares: The Invention of Morel

Max Blecher: Scarred Hearts

Nicolas Born: The Deception

Thomas Brasch: Vor den Vätern sterben die Söhne

Joseph Brodsky: On Grief and Reason

Alina Bronsky: Just Call Me Superhero

Alina Bronsky: The Hottest Dishes of the Tartar Cuisine

Dino Buzzati: The Tartar Steppe

Leila S. Chudori: Pulang

Beqe Cufaj: projekt@party

Mahmoud Darwish: Memory of Forgetfulness

Oei Hong Djien: Art & Collecting Art

Dimitre Dinev: Engelszungen (Angel’s Tongues)

Anton Donchev: Time of Parting

Jabbour Douaihy: June Rain

Michael R. Dove: The Banana Tree at the Gate

Jennifer DuBois: A Partial History of Lost Causes

Isabelle Eberhardt: Works

Tristan Egolf: Lord of the Barnyard

Deyan Enev: Circus Bulgaria

Jenny Erpenbeck: The End of Days

Patrick Leigh Fermor: Mani

Milena Michiko Flašar: I called him Necktie

David Fromkin: A Peace to End All Peace

Carlos Fuentes: Terra Nostra

Amitav Ghosh: In an Antique Land

Georg K. Glaser: Geheimnis und Gewalt (Secret and Violence)

Georgi Gospodinov: Natural Novel

Georgi Gospodinov: The Physics of Sorrow

Elizabeth Gowing: Edith and I

David Graeber: The Utopia of Rules

Garth Greenwell: What Belongs to You

Knut Hamsun: Hunger

Ludwig Harig: Die Hortensien der Frau von Roselius

Johann Peter Hebel: Calendar Stories

Christoph Hein: Settlement

Wolfgang Hilbig: The Sleep of the Righteous

Albert Hofmann / Ernst Jünger: LSD

Hans Henny Jahnn: Fluss ohne Ufer (River without Banks) (Part II)

Franz Jung: Der Weg nach unten

Ismail Kadare: Broken April

Ismail Kadare: The Palace of Dreams

Douglas Kammen and Katharine McGregor (Editors): The Contours of Mass Violence in Indonesia: 1965-1968

Rosen Karamfilov: Kolene (Knees)

Orhan Kemal: The Prisoners

Irmgard Keun: Nach Mitternacht

Georg Klein: Libidissi

Friedrich August Klingemann: Bonaventura’s Nightwatches

Fatos Kongoli: The Loser

Theodor Kramer: Poems

Friedo Lampe: Septembergewitter (Thunderstorm in September)

Clarice Lispector: The Hour of the Star

Naguib Mahfouz: The Cairo Trilogy

Curzio Malaparte: Kaputt

Thomas Mann: Joseph and His Brothers

Sandor Marai: Embers

Sean McMeekin: The Berlin-Baghdad Express

Multatuli: Max Havelaar

Alice Munro: Open Secrets

Marie NDiaye: Three Strong Women

Irene Nemirovsky: Suite française

Ben Okri: The Famished Road

Laksmi Pamuntjak: The Question of Red

Victor Pelevin: Omon Ra

Georges Perec: Life. A User’s Manual

Leo Perutz: By Night Under the Stone Bridge

Boris Pilnyak: Mahogany

Alek Popov: Black Box

Milen Ruskov: Thrown Into Nature

Boris Savinkov: Memoirs of a Terrorist

Eric Schneider: Zurück nach Java

Daniel Paul Schreber: Memoirs of My Nervous Illness

Carl Seelig: Wandering with Robert Walser

Victor Serge: The Case of Comrade Tulayev

Anthony Shadid: House of Stones

Varlam Shalamov: Kolyma Tales

Raja Shehadeh: A Rift in Time

Alexander Shpatov: #LiveFromSofia

Werner Sonne: Staatsräson?

Andrzej Stasiuk: On the Way to Babadag

Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar: The Time Regulation Institute

Pramoedya Ananta Toer: A Mute’s Soliloquy

Pramoedya Ananta Toer: The Buru Quartet (4 vol.)

Lionel Trilling: The Middle of the Journey

Iliya Trojanov: The Collector of Worlds

Bernward Vesper: Die Reise (The Journey)

Robert Walser: Jakob von Gunten

Peter Weiss: The Aesthetics of Resistance

Edith Wharton: The Age of Innocence

Marguerite Yourcenar: Coup de Grace

Galina Zlatareva: The Medallion

Arnold Zweig: The Case of Sergeant Grisha

Stay tuned – and feel free to comment any of my blog posts. Your contributions are very much appreciated. You are also invited to subscribe to this blog if you like.

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-5. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter