Moritz Daniel Oppenheim was an important German painter of the 19th century. He was probably the first Jewish visual artist to gain world renown. At an advanced age, he wrote an autobiography intended as a memoir for his family; it was not published during his lifetime. In 1924, his grandson Alfred Oppenheim, who was also a painter, published the manuscript as a book; it was reprinted in 1999 and 2013.

According to family memories, Oppenheim was born in late December 1799 in Hanau, a town east of Frankfurt am Main. (Wikipedia and other sources report a date of birth at the beginning of January 1800.) His Jewish family lived in economically relatively secure conditions, even though the Hanau Jews still had to live in the ghetto at that time and had to face a variety of discriminations. Although the legal betterment of the Jews in Germany at this time made progress in the wake of the emancipatory efforts of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing or Moses Mendelssohn, and especially after the French Revolution, it should nevertheless take decades before the legal equality of Jews in Germany was realized. Oppenheim’s autobiography is so interesting because it not only traces an individual artist’s life, but because it is also a practical example of how this process of Jewish emancipation in Germany in the 19th Century progressed: slowly and characterized by numerous setbacks.

A relatively big part of Oppenheim’s autobiography is devoted to his childhood and youth. Loving and caring parents who focused on providing their children with a good education evidently laid the foundation for his well-balanced character and for being knowledgeable about many subjects, not only about those necessary for a later career. Oppenheim attended the local Talmud Torah school, but received also private lessons. Later he went to a regular high school, together with Christian students. In addition, he and one of his brothers received permission from the father to attend the local drawing academy, where his artistic talent showed early; but young Moritz Daniel didn’t initially plan a professional future as an artist – he originally wanted to become a doctor. From his mother, the young Oppenheim inherited his love for literature and theater – the mother read for example Goethe’s Hermann and Dorothea and attended sometimes theater performances together with her son; these visits inspired Moritz Daniel to set up a puppet theater in the attic of their home (this feels a bit reminiscent of Wilhelm Meister).

What follows are the years at the Hanau and later at the Munich Academy, in which Oppenheim trains his talent as a draftsman and in oil painting. In retrospect, Oppenheim remembers his teachers and supporters of that period with warmth and gratitude, but he also peppers his memoirs with a few humorous anecdotes. The self-portrait, which he created as a 16-year-old, is already proof of his considerable talent and self-confidence.

To broaden his horizons Oppenheim studied afterwards in Paris and later in Italy, the country for which so many German artists of his time were yearning. In Paris, he seems to have been a frequent visitor of the legendary Café de la Régence; in his biography he mentions the meeting with Aaron Alexandre there, a rabbi born in Germany, who emigrated to France during the French Revolution and who is remembered today mainly as the author of the monumental chess problem book Collection des plus beaux Problèmes d’Echecs. Alexandre was considered to be one of the world’s best chess players of his time.

More productive in artistic terms was for Oppenheim his subsequent longer stay in Italy. He attached himself looseley to the circle of the Nazarenes, an art movement that exercised a certain influence on him, but which he quickly outgrew. Particularly valuable was in addition to his contacts with Friedrich Overbeck in Rome especially the friendship with the then already famous Bertel Thorvaldsen. The senior Danish sculptor and draftsman was in Rome something like Oppenheim’s artistic mentor, and he provided artistic guidance as well as contacts with potential customers who would be interested to buy Oppenheim’s works.

If Oppenheim had expected that he would not experience any anti-Jewish resentment among fellow artists in his Italian environment, he was wrong. Both among his colleagues and among Italian acquaintances, he experienced frequently more or less open exclusion as soon as he was recognized as a Jew. In order to avoid this exclusion, several painters of Jewish origin converted to Christianity at that time (as did also the writers Heinrich Heine and Ludwig Börne). Oppenheim, who was obviously much more deeply rooted in Judaism than many others, did not follow this path. He managed to gain broad recognition and success in his later life as a Jewish painter in Germany.

One can attest Oppenheim an excellent sense of the social position of his clients and other people important for his advancement. He almost effortlessly won major Jewish art collectors, such as those from the Rothschild family, as buyers for portraits. When the still rather young Oppenheim visited Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in Weimar in 1827 – the visit was preceded by an exchange of letters in which Goethe apparently obtained a positive impression of the young man’s talent and character -, he was awarded at Goethe’s request with an order and a paid professorship with no teaching commitments. From that moment on, Oppenheim was a man who became known in important circles also outside the Jewish community.

What followed was a very successful life as an artist; Oppenheim presents himself as a man for whom a fulfilled family life was very important and he also seems to have lived in great harmony as a husband (after the early death of his first wife, he married a second time) and father of six children. I found this second part of the autobiography – apart from the sections on the 1848/49 revolution – a little less interesting, although all in all this brief autobiography is an important and instructive document.

Here are a few more of Oppenheim’s works. He was particularly popular as a portrait painter, as the following three portraits of writers illustrate:

Scenes from Jewish life in Germany were another frequent subject of Oppenheim’s artworks. Prints based on Oppenheim’s paintings were a frequent adornment of many Jewish homes in the 19th and 20th centuries. They not only showed the everyday life of Jewish families who succeeded to leave the ghetto behind, but would also provide a clear message – particularly in the next painting -: that it is possible to be a Jew, following the religious norms of the forefathers, and at the same time to be a German patriot, fighting as a volunteer in the War of Liberation:

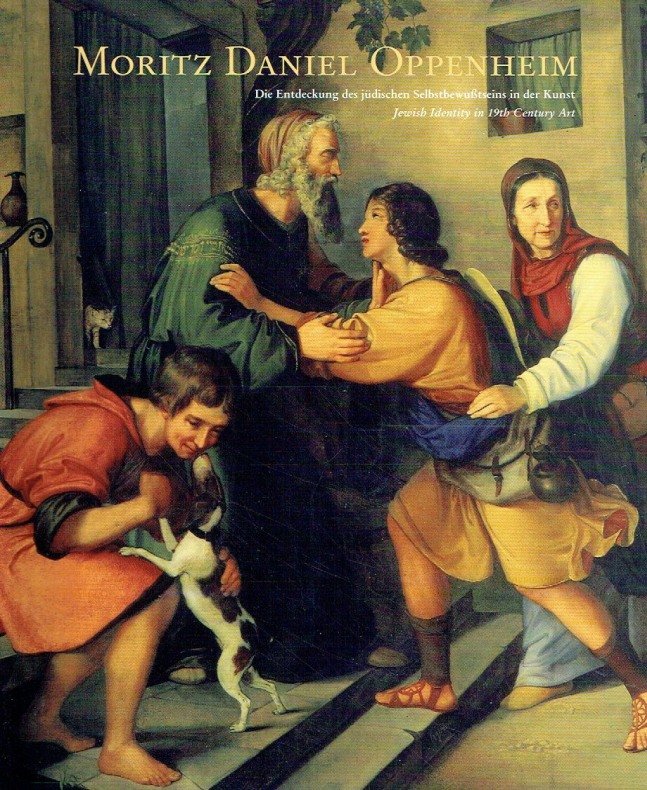

While Oppenheim’s autobiography seems to be untranslated, the following bi-lingual catalogue contains not only a detailed biography and essays about his art, but also reproductions of most of his works and is therefore highly recommended for anyone with an interest in this important German-Jewish artist.

Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, Erinnerungen eines deutsch-jüdischen Maler (Memoirs of a German-Jewish Painter), Manutius, Heidelberg 1999

Georg Heuberger / Anton Merk (eds.), Moritz Daniel Oppenheim. Die Entdeckung des jüdischen Selbstbewußtseins in der Kunst /Jewish Identity in 19th Century Art, Jüdisches Museum Frankfurt am Main 1999 (bi-lingual German/English)

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-20. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter