The year 2019 is almost over and it is time to look back at my reading and blogging experiences.

After a hiatus, I started again to blog more or less regularly and I hope this will be also the case for 2020.

As for my reading, I didn’t keep a diary to track down the books I read this year, but the number is approximately 130, so roughly two and a half books per week, of which around 60% were fiction, 40% non-fiction. Almost all books I read were “real” printed books, only one book was read electronically. I read books in four languages (German, English, French, Bulgarian).

Every book year brings interesting discoveries, pleasant surprises, some re-reads of books I enjoyed in the past, and a few disappointments. Here are my highlights of the last year:

The most beautiful book I read in 2019: Arnulf Conradi, Zen und die Kunst der Vogelbeobachtung (Zen and the Art of Birdwatching)

Best re-reads in 2019: Michel de Montaigne, Essais; Karl Philipp Moritz, Anton Reiser; Salomon Maimon, Lebensgeschichte (Autobiography)

Best novels I read in 2019: Marlen Haushofer, Die Wand (The Wall); Uwe Johnson, Jahrestage (Anniversaries); Jean Rhys, Sargasso Sea

Best poetry books I read in 2019: Thomas Brasch: Die nennen das Schrei (Collected Poems); Johannes Bobrowski, Gesammelte Gedichte (Collected Poems), Franz Hodjak, Siebenbürgische Sprechübung (Transylvanian Speaking Exercise); Yehuda Amichai, The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai; Anise Koltz, Sich der Stille hingeben (Surrender to the Silence); Mahmoud Darwish, Unfortunately It Was Paradise; Vladimir Sabourin, Останките на Троцки (Trotzky’s Remains); Rainer René Mueller, geschriebes, selbst mit stein

Best Graphic Novel I read in 2019: Art Spiegelman, Maus

Best SF novel I read in 2019: Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, The Doomed City

Best crime novel I read in 2019: Ingrid Noll, Halali

Best philosophy book I read in 2019: Ibn Tufail, The Improvement of Human Reason

Best non-fiction books I read in 2019: Charles King, The Moldovans; Charles King, Midnight at the Pera Palace; Timothy Snyder, The Road to Unfreedom; Adriano Sofri, Kafkas elektrische Straßenbahn (Kafkas Electric Streetcar); Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide to Getting Lost; Lucy Inglis, Milk of Paradise; Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole, Sacred Trash; Sasha Abramsky, The House of Twenty Thousand Books

Best art book I read in 2019: Hans Belting, Der Blick hinter Duchamps Tür (The View behind Duchamp’s Door)

Best travel book I read in 2019: Johann Gottfried Seume, Spaziergang nach Syrakus (Walk to Syracuse)

Biggest book disappointment in 2019: Elena Ferrante, Neapolitan Novels

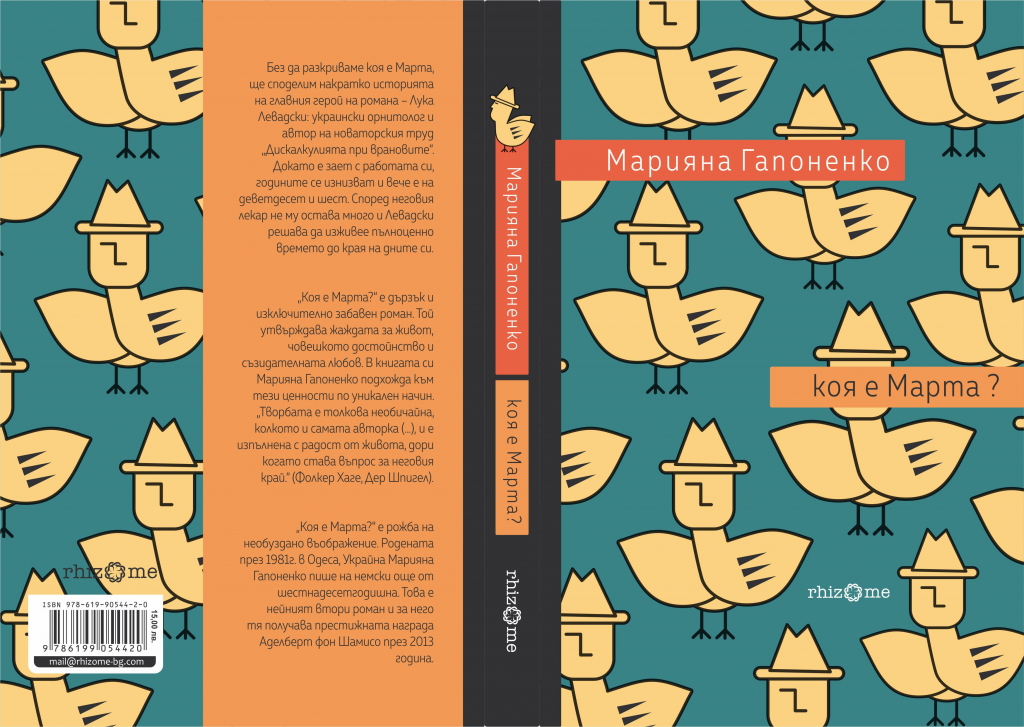

Favourite book cover in 2019: Ivo Rafailov’s cover for the Bulgarian edition of Marjana Gaponenko’s Who Is Martha? (this edition is upcoming in January 2020)

Most impressive translator’s work: Jennifer Croft’s translation of Flights by Olga Tokarczuk; Vladimir Sabourin’s translations in his Bulgarian poetry anthology Радост на Началото (The Joy of the Beginning)

Most embarrassing authors in 2019: Peter Handke; Christoph Hein; Zachary Karabashliev

Good as always: Vladimir Sorokin, The Blizzard; Clarice Lispector, Near to the Wild Heart; Ismail Kadare, The Traitor’s Niche; Jabbour Douaihy, Printed in Beirut; Georg Klein, Die Zukunft des Mars (The Future of the Mars); Phillipe Claudel, Le rapport de Brodeck (Brodeck), Kapka Kassabova, Border; Naguib Mahfouz, The Midaq Alley

Interesting Authors I discovered in 2019: Samanta Schweblin, Mouthful of Birds; Olga Tokarczuk, Flights; Isabel Fargo Cole, Die Grüne Grenze (The Green Border); Hartmut Lange, Das Haus in der Dorotheenstraße (The House in the Dorotheenstraße); Erich Hackl, Abschied von Sidonie (Farewell to Sidonia)

And which were your most remarkable books in 2019?

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-9. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter