There are numerous volumes on art and artists on my bookshelf – exhibition catalogues, biographies, monographs, essays, art theoretical writings and more. If I wrote in my last post that bookstores are among the first places that I explore in a city that is new to me, the same can be saidfor galleries and art museums. It is therefore not surprising that I am following this example in Dhaka as well.

An opulent, heavy and elaborately designed volume about the painter Safiuddin Ahmed was one of the first that I bought in Dhaka. Safiuddin Ahmed was born in Calcutta in 1922 and died in Dhaka in 2012. He had lived in East Pakistan, later Bangladesh, since 1947.

Ahmed came from an educated and devout but liberal Muslim family in Kolkata. After the early death of the father, the mother raised her children alone. Safiuddin showed early talent and interest in drawing; one of his later teachers at the art academy, convinced his mother against her initial resistance to allow her son to become an artist.

A catalog essay by the poet Kaiser Haq goes into the historical background and context, especially of the artist’s younger years. These were years of political debates about the future of British India, the notorious famine years, fights about the relationship between the different religions and the different ethnic groups, but also about the subtle racism of the British colonial rulers, which was also reflected in the art education. Just before the painter began his studies it was heavily focused on handicrafts and was oriented exclusively to western traditions, since the locals were denied any true understanding of art. But Ahmed was lucky – he benefited from the reform efforts of the 1930s, which brought about a departure from this pattern, and above all from exceptionally good teachers, about whose importance the painter gives moving expression in an interview printed in the volume.

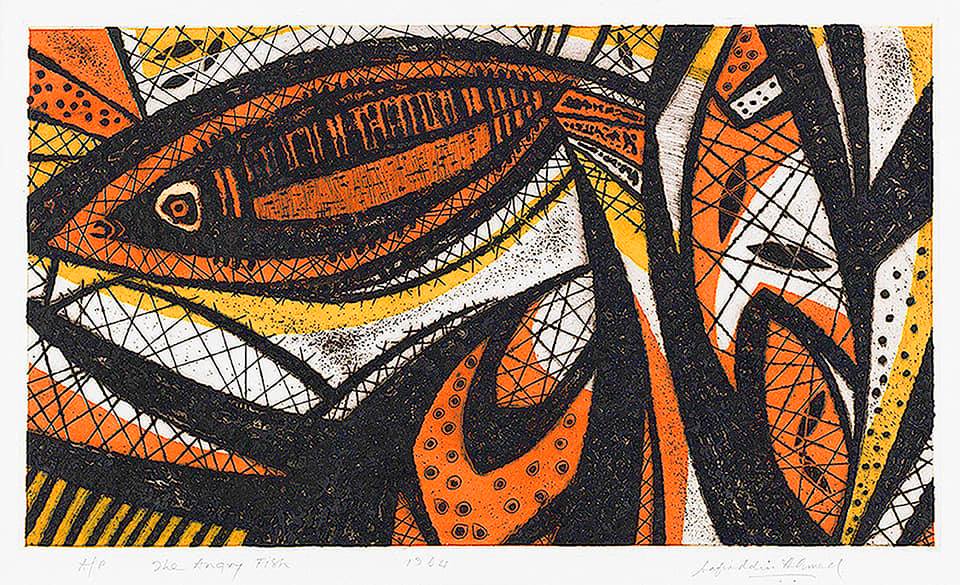

After the partition of Bengal (and India) in 1947, Ahmed settled in Dhaka, East Bengal, which at the time was still a relatively small city without an art scene comparable to Calcutta. With some other painters, emigrants from Calcutta like himself, he founded the first art school in Dhaka, which is now a separate faculty of Dhaka University. Ahmed taught printmaking here, a technique he had taught already briefly in Calcutta and for which he was particularly talented.

What follows is an artist career in quite difficult conditions: politically due to the suppression of the Bengali language and culture by West Pakistan, and the later, extremely bloody Bangladesh independence struggle in 1971; but also because of arguments about the role of the artist in society; several heavy floods, in which part of his work was lost, also contributed to the fact that the artist led a rather eventful, not easy life.

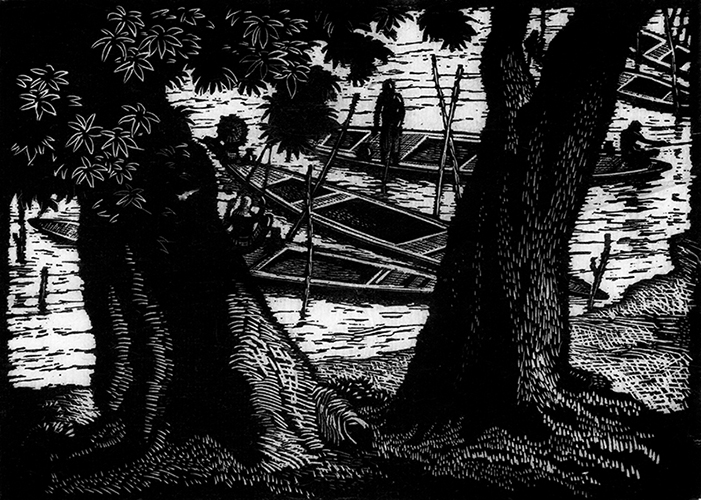

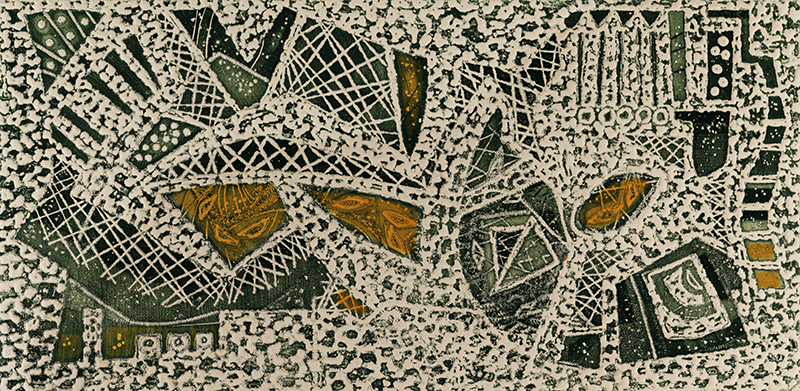

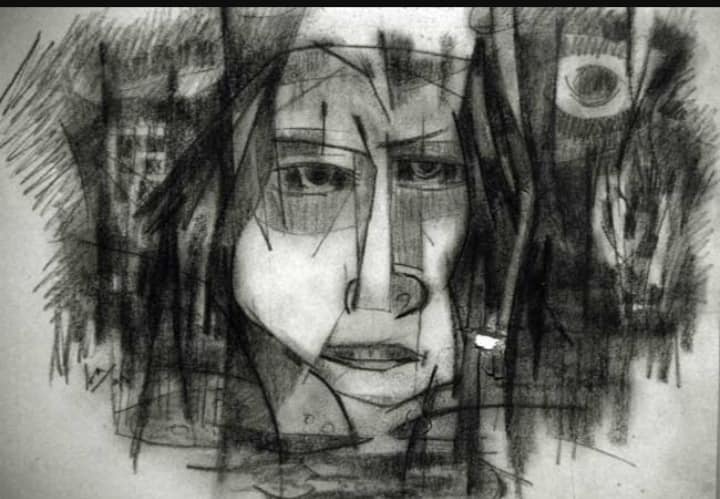

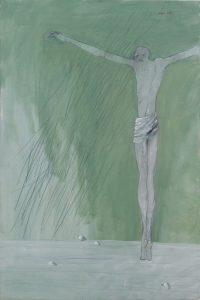

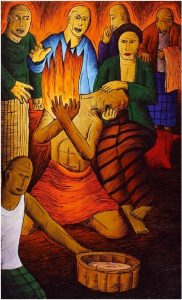

A longer catalog essay by Syed Azizul Haque deals with Safiuddin Ahmed’s artistic career. Themes from everyday life in the village, portraits, sketches of nudes, semi-abstract works, still lifes and repeated scenes in which water plays a major role – Ahmed, who had empathy for ordinary people and was personally very humble, had a broad range of topics.

A great diversity can also be seen in the techniques he used. Drawings, watercolours, woodcuts, drypoint etchings and aquatints, engravings – a technique he learned during a long stay in London – and oil paintings show his versatility here too. His preference for the color black, which plays a central role in many of his works, is striking, as is his interest in learning new techniques or perfecting them, even as he gets older.

Decades of teaching enabled Ahmed to earn a regular income and therefore he rarely needed to sell any of his work. In the interview mentioned above, he says:

„I love my creations and don’t wish to part with them…I have no desire to sell paintings to those who collect them in order to boost their social status.”

The works presented in this blog post are from the Estate von Safiuddin Ahmed. You can see more of his work on a website dedicated to him. Or even better: you get a copy of this beautiful book!

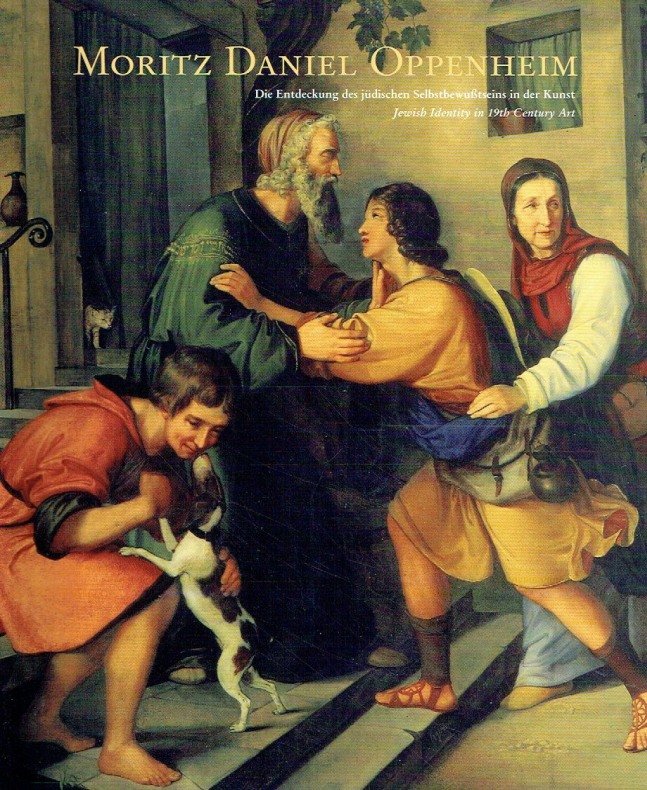

Rosa Maria Falvo (ed.) with an introduction by Kaiser Haq and an essay by Syed Azizul Haque: Safiuddin Ahmed, Skira / Bengal Foundation, Milano / Dhaka 2011

© The estate of Safiuddin Ahmed, 2011 © Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-22. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter