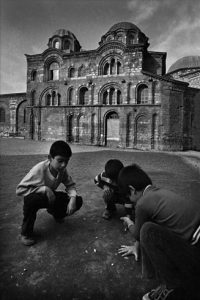

As readers of Andre Aciman’s wonderful memoir Out of Egypt will know, Egypt was until the 1950s home of a Levantine Jewish community that lived for most of its history comparatively well integrated and respected in this part of the world.

Multi-cultural Cairo and Alexandria were at that time home to many religious and ethnic minorities that over the centuries had learned to cope with each other in a – mostly – peaceful way. Many members of the Jewish community like the Cattaui family had risen to great wealth and affluence. With the rise of Egyptian nationalism, the wars in 1948 and 1956 and the erection of an authoritarian regime of officers under the leadership of Nasser, this period came abruptly to an end. The Jews were no longer welcome in Egypt and had to leave, usually with very little except their lives and a few clothes.

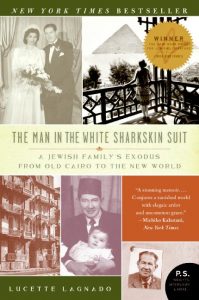

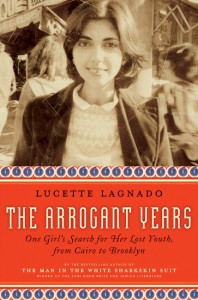

This is the historical backdrop of two books of memoirs by Lucette Lagnado, The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit and The Arrogant Years. Lagnado, a journalist working for major newspapers like the Wall Street Journal, was born in Egypt, where she spent her first years before emigrating via France to the US with her parents and siblings.

The books are covering roughly a century. Whereas The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit focuses mainly on her father, The Arrogant Years is mainly devoted to the life of the author’s mother. Although the two works cover the same period, Lagnado avoids redundancy as much as possible which makes both books worth reading.

The author’s father, Leon, was obviously a larger-than-life figure: he was very tall, good-looking, with impeccable manners and a talent for languages; a boulevardier that liked to go out every evening until late at night; a business man that was so secretive about his business that even his close family members had no idea if his business was thriving or if he was on the verge of bankruptcy; a womanizer that was rumored to have had many affairs (including the charismatic singer Om Kalthoum); a man that was at home with the British officers in Cairo during WWII who dubbed him “the Captain”; but at the same time a devout Jew who observed all rules of his creed and was praying every day in the synagogue; a patriarch with a very traditional mindset when it came to the role of women in the family; but at the same time a very kind and patient father (especially with his youngest daughter, the author).

Edith, the author’s mother, was considerably younger than her husband. Although her background was very different from Leon’s – her family was very poor -, her charm and good looks, together with her good education and humble manners made Leon approach her. The first chapter of Sharkskin which describes the courting makes quite an entertaining read. There was not much romance, the whole affair was conducted in a quite businesslike way by Leon and Alexandra, Edith’s mother, who set the rules for the further proceedings.

But the marriage proved to be a rather unhappy affair. Leon didn’t change his lifestyle of going out late every evening (except Sabbath) without his wife. Edith, who had worked as a very young teacher and librarian for the Cattaui family, the most influential Jewish family in Egypt, had to give up her job she loved so much and was confined to the home where she was supposed to take care of the children and the household, which was de facto dominated by Leon’s mother, a rather stern woman from Aleppo who insisted to speak only Arabic (usually Levantine families like the Lagnados would speak French as native language).

Both parents felt deeply enrooted in Egypt. While more and more of their friends and relatives were leaving the country, they tried to hold out as long as possible. But after a short arrest of the oldest sister Suzette, it is obvious that they have to leave. In Paris, the family which is now completely depended on the support by some organizations that deal with Jewish refugees, has to wait quite a long time until finally being admitted to be resettled in the US.

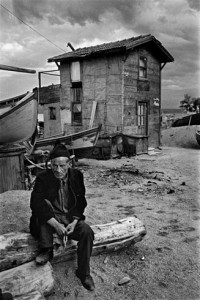

Life in New York held many difficulties in stock for the Lagnados: Leon, once a quite wealthy and successful businessman, had to support his family with the small earnings he made as a street seller of fake silk ties; the mother’s dream “to rebuild the hearth” fell apart since the older children were step by step going their own way or even leaving home for good. Life in Cairo was better in so many respects for the older generation and the nostalghia they are feeling in relation to their home country doesn’t exactly help them to embrace the American Way of Life that seems so strange to them.

While the author’s father seems to get tired from life and is withdrawing more and more to his prayer books, Edith surprisingly re-invents herself. She applies for a library job and despite lacking degrees or practical experience (except for her work as a young girl in the Cattaui library), she is surprisingly hired. From the author’s descriptions it becomes clear that this – beside her childhood – was probably the happiest time in the life of her mother, who deeply loved (mainly French) literature and who had read the complete Marcel Proust already as a young girl in Cairo.

Lagnado’s books touch on many interesting issues: the school and university system in the US; the typical problems of immigrant children who “try to fit in”; the change of the role of women in family and society that started in the 1960s with the Women’s Lib movement; the role of tradition and religion in the Jewish community; and also the situation of the health sector in the States. Quite a lot of the books deal with the ailments of her parents and herself (Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s in the case of Leon; a series of debilitating strokes in the case of Edith; and Hodgkin’s disease in the case of the author). But that’s not a criticism: this family has had more than their fair share of sufferings.

Lagnado’s books are not only a monument for her parents, but also for a now almost extinct specific Levantine Jewish culture. At the end of both books, she is able to reconnect herself with her own past and the past of this community. After many years, she is visiting Cairo again, standing on the balcony of her former family home in Malaka Nazli (now: Ramses) Street. And somewhere in Switzerland she tracks down the remains of the famous Cattaui library, including the books that were purchased decades ago by her mother who was given the key to the legendary Pasha’s library by the famous Madame Cattaui.

As readers we can feel rewarded that Lagnado shared her family history with us and we can be glad that she was able to make new friends again in her native city. Two truly remarkable and touching memoirs.

Lucette Lagnado: The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit, Ecco Press, New York 2007

Lucette Lagnado: The Arrogant Years, Ecco Press, New York 2011

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter