Nachdem zwei frühere Auswahlbände mit Gedichten von Paul Celan aus den Jahren 1998 und 2002 längst vergriffen sind, ist es ein erfreuliches Ereignis, dass Ende 2019 erneut ein Band mit ausgewählten Gedichten Celans in bulgarischer Übersetzung vorliegt. Grund genug für mich, mir diese Ausgabe anzuschaffen. Ein paar Gedanken zu diesem Buch:

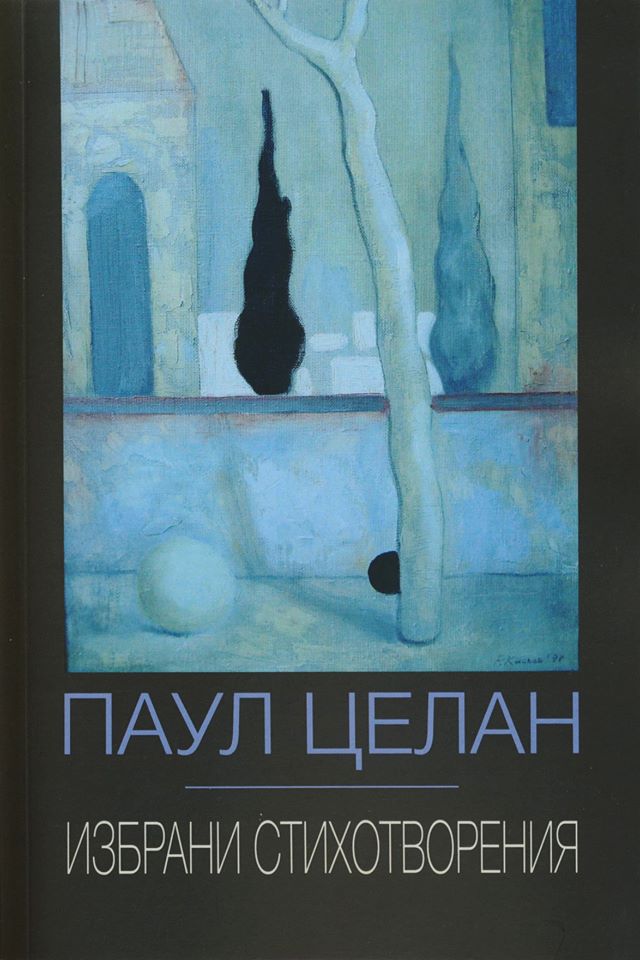

Zunächst einige Äußerlichkeiten, die mir allerdings bei einem Werk gerade eines mir so kostbaren Autors wie Celan wichtig sind. Der vorliegende Band ist handwerklich offenbar gut gemacht und hat eine ansprechende Einbandgestaltung (unter Verwendung eines Gemäldes des Dichters Roman Kissiov). Sehr erfreulich ist die Tatsache, dass es sich um eine zweisprachige Ausgabe handelt; der des Deutschen kundige Leser kann hier jeweils direkt das Original und die Übersetzung, die sich im Druckbild gegenüberstehen, miteinander vergleichen. Für die Entscheidung, die Gedichte auch im deutschen Original zu bringen, ist der Verlag sehr zu loben. Ich würde mir derartige zweisprachige Ausgaben auch in anderen vergleichbaren Fällen wünschen.

Auch die Auswahl der in den Band aufgenommenen Gedichte erscheint mir im allgemeinen gelungen; es versteht sich von selbst, dass jeder Celan-Leser seine Lieblingsgedichte hat, die er gerne in einem solchen Band sehen möchte. Und es versteht sich ebenfalls von selbst, dass jede Auswahl subjektiv ist und daher auch der neue Band ein paar aus meiner Sicht bedauerliche Lücken hat. Vor allem das Fehlen des Gedichts „Todtnauberg“, das auf Celans sehr wichtige Begegnung mit Martin Heidegger anspielt und in seinem Werk eine Schlüsselstellung einnimmt, erscheint mir allerdings als ein wirkliches Manko. Ein grosses Plus wiederum ist die Tatsache, dass Celans einzige längere programmatische Äußerung zu seiner eigenen Lyrik, die „Meridian“-Rede, die er 1960 in Darmstadt anlässlich der Verleihung des Georg-Büchner-Preises hielt, in den Band aufgenommen wurde.

Celan ist für jeden Übersetzer, der sich an seinem Werk versucht, eine Herausforderung. Er ist aus verschiedenen Gründen schwer zu übersetzen bzw. nachzudichten. Das gilt besonders für seine späten Gedichte, in denen die Syntax und die Sprache allgemein immer stärker „aufgebrochen“ wird und die bei Celan ohnehin vorhandene Tendenz zu grosser Ambiguität hinsichtlich der Aussage und des Inhalts der Gedichte oft so weit getrieben wird, dass der Leser vor großen Herausforderungen steht. Dass die Übersetzerin Maria Slavcheva sich trotzdem an das Werk dieses sehr komplexen Dichters gewagt hat, verrät Mut und eine gute Portion Selbstbewusstsein.

Literarisches Übersetzen, zumal von Lyrik, erfordert vom Übersetzer viele zum Teil schwierige Entscheidungen zu treffen. Bei der Besprechung der Übersetzung eines Lyrikbandes sollte es daher auch darum gehen, ob die vom Übersetzer getroffenen Entscheidungen in der Regel plausibel oder nicht plausibel sind. (Es gibt hier oft kein klares „richtig oder falsch“; von groben sinnentstellenden Fehlern einmal abgesehen.) Mein persönliches Urteil ist hier überwiegend positiv: in vielen der übersetzten Gedichte trifft die Übersetzerin den Sinngehalt und auch die Form, die Celans Original vorweist. Einige kritische Anmerkungen sollen allerdings an dieser Stelle nicht verschwiegen werden.

Celans wohl berühmtestes Gedicht „Todesfuge“ ist wahrscheinlich auch sein am häufigsten übersetztes. Auf bulgarisch kenne ich ein halbes Dutzend verschiedene Übersetzungen dieses Gedichts, von denen mir die Version von Emanuil Vidinski als die mit Abstand gelungenste erscheint. Im Original finden sich diese Zeilen:

„… der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland sein Auge ist blau / er trifft dich mit bleierner Kugel er trifft dich genau…“

Die Tatsache, dass Celan hier – aber eben auch nur hier – einen Endreim in diesem Gedicht verwendet, deutet auf die geradezu zentrale Rolle dieser beiden Zeilen im Gedicht hin. Der Endreim ist kein Zufall – wie ja auch sonst nichts in den Gedichten Celans Zufall ist.

In der vorliegenden Ausgabe werden diese Zeilen wie folgt übersetzt:

“…смъртта е майстор от Германия със сини очи / той те улучва с оловен куршум улучва те точно…”

Im Vergleich dazu heißt es bei Vidinski:

„…смъртта е германски маестро окото му е синьо / улучва те с оловен куршум улучва те точно…“

Die zweite Variante ist sowohl sprachlich näher beim Original, als auch hinsichtlich Reim und Rhythmus des Gedichts eindeutig vorzuziehen.

Neben einigen weiteren für mich schwer nachvollziehbaren Entscheidungen gerade bei diesem Gedicht, hat die Übersetzerin unglücklicherweise einen meiner Meinung nach ausgesprochen schweren Lapsus in der bulgarischen Fassung der „Todesfuge“ begangen, der durchaus in den Sinngehalt des Gedichts eingreift und welcher Leser, die mit Celan und seiner Geisteswelt nicht oder wenig vertraut sind, auf eine vollkommen falsche Spur führt.

Wenn Celan in dem Gedicht

„dein goldenes Haar Margarete / dein aschenes Haar Sulamith“

schreibt, evoziert er damit eben nicht nur irgendeine blonde (deutsche) Margarete und irgendeine (jüdische) Sulamith mit aschfarbenem Haar, sondern er spielt natürlich auf Margarete aus Goethes „Faust“ und Sulamith aus dem Hohen Lied Salomos an, zwei emblematische Dichtungen für das deutsche und das jüdische Volk – wie ja überhaupt, das Deutsche und das Jüdische bei diesem Dichter geradezu schicksalhaft miteinander verwoben waren.

Celan, der die Möglichkeiten deutscher Dichtung nach dem Holocaust erneuert und erweitert hat wie kein Zweiter, beherrschte die deutsche Sprache virtuos; zu den Schuldgefühlen, die er wegen des Todes seiner Eltern hatte, gesellten sich gerade deshalb die Schuldgefühle, in der Sprache der Mörder seiner Eltern zu dichten und seine meisten Leser im Land der Täter zu haben. Wenn die Übersetzerin in ihrer Fassung aus Margarete eine Margarita macht (твоята златна коса Маргарита / твоята пепелива коса Суламит), verfälscht sie die Aussage des Gedichts vollkommen; der Leser wird vielleicht an Bulgakov denken, aber mit der offensichtlichen Autorintention von Celan hat das absolut nichts zu tun. Ein wirklich unnötiger und sehr schwerer Fehler in meinen Augen (den auch Tekla Sugareva und Edvin Sugarev in ihrer Version seinerzeit gemacht haben), der die Vermutung nahelegt, dass die Übersetzerin wohl mit den Hintergründen von Celans Dichtung verhältnismäßig wenig vertraut ist.

Gestolpert bin auch über eine Fußnote zu einem der zentralen Gedichte Celans, „Mandorla“. In der Fußnote erfährt der Leser, dass Mandorla die „mandelförmige Aureole, die in der christlichen Ikonographie verwendet wird“ sei. Zwar ist es zutreffend, dass der Heiligenschein christlicher Heiligenbilder als Mandorla bezeichnet wird; trotzdem ist die Fußnote irreführend, da eben nicht nur in der christlichen Ikonographie eine solches mandelförmiges Halo verwendet wird. Es findet sich unter anderem auch im Buddhismus und – für Celan sicher sehr wichtig – in der Kabbala, der jüdischen Mystik.

Das Gedicht „Mandorla“ gehört wohl zu den am schwersten zu deutenden Gedichten Celans und ich will mich hier keineswegs an einer weiteren Deutung versuchen. Eine Anmerkung, die den Eindruck erweckt als habe sich Celan hier eindeutig auf die christliche Ikonographie bezogen, führt den Leser aber in die Irre. Eine solche Eindeutigkeit ist der Dichtung Celans wesensfremd; darauf hat zu Recht Hermann Detering in seinem Aufsatz „Religionsgeschichtliche Anmerkungen zu Paul Celans Gedicht „Mandorla““ hingewiesen – aus dem Gedicht selbst lässt sich die in der Fußnote der Buchausgabe suggerierte Eindeutigkeit keineswegs ableiten. Anmerkungen sollen dem Verständnis des Lesers dienen; die hier angesprochene Fußnote tut dies nicht, sie führt im Gegenteil den Leser zu einer abwegigen und verengenden Lektüre des Gedichts.

Überhaupt, die Fußnoten. Nach meinem Eindruck sind sie manchmal überflüssig, an anderen Stellen, wo sie auf bestimmte Bezüge von Celans Dichtung erklärend hinweisen könnten, die den meisten bulgarischen Lesern nicht geläufig sind, fehlen sie. Dazu ein Beispiel aus dem Nachwort des Bandes, das wie folgt beginnt:

„Jedem Text bleibt sein „20. Jänner“ eingeschrieben. Wenn auch an einem 23. April begonnen trägt auch diese Übersetzung einen „20. Jänner“ in sich, von dem Celan sich herschrieb.“

In einer Fußnote erläutert die Übersetzerin, dass der 23. April der Welttag des Buches sei. Inwieweit dies für das Verständnis von Celan bzw. für den Leser von Interesse ist, ist mir schleierhaft. Viel wichtiger wäre eine Anmerkung gewesen, die den Bezug zu der Behauptung der Übersetzerin erläutert, dass sich Celan von einem „20. Jänner herschrieb“. Ich vermute stark, dass den bulgarischen Lesern in der Regel vollkommen unverständlich ist, was es mit diesem 20. Jänner im Zusammenhang mit Celans Dichtung auf sich hat. Zwar steht als Motto über dem Nachwort ein Zitat aus Celans Meridian-Rede in der er fragt

„Vielleicht darf man sagen, dass jedem Gedicht sein „20. Jänner“ eingeschrieben bleibt?“,

allerdings ist dies nicht dasselbe wie die Behauptung, Celan habe sich „von einem „20. Jänner“ hergeschrieben“.

Was also hat es mit diesem 20. Jänner auf sich (Celan verwendet sowohl in der Meridian-Rede als auch im Gedicht „Tübingen, Jänner“ diese eher ungewöhnliche regionaltypische Form des Monatsnamens Januar, was allein schon ein deutlicher Hinweis ist)? Eine Fußnote hätte hier deutlich mehr Nutzen gestiftet als das später im Nachwort folgende Namedropping – Szondi, Gadamer, Derrida, Hamburger (die Hinweise auf Ingeborg Bachmann und Bertolt Brecht sind dagegen angebracht, da es einen konkreten Bezug von im Band abgedruckten Gedichten gibt).

Dass der „20. Jänner“ sich auf den Anfang von Georg Büchners Erzählung „Lenz“ bezieht – wie viele bulgarische Leser wissen das? Und dass das Gedicht „Tübingen, Jänner“ auch darauf anspielt (Hölderlin war ein interessierter Leser von Lenz und erlebte ähnliche lebensgeschichtlich bedeutsame Enttäuschungen mit den Weimarer Titanen Schiller und Goethe) und dies ebenso wie die programmatische Rede Celans als Auseinandersetzung mit den Klassikern der deutschen Dichtung und als Gegenposition zu deren Dichtungsverständnis gesehen werden muss, gegen das sich die Lenz, Hölderlin, Büchner gewandt haben – auch dies hätte man gerne in einem solchen Nachwort, das leider sehr an der Oberfläche bleibt, gelesen.

Mein Urteil über diese Ausgabe ist – daran möchte trotz der oben angeführten Kritik keinen Zweifel lassen – insgesamt eher positiv. Eine überwiegend respektable Übersetzerleistung, die aber nicht in jedem Gedicht das hohe Niveau hält. Das Beiwerk (Fußnoten und Nachwort) finde ich fast ein wenig ärgerlich. Eine Ausgabe, die ganz darauf verzichtet hätte, wäre aus meiner Sicht vorzuziehen gewesen.

Wie ich gehört habe, soll eine weitere bulgarische Celan-Ausgabe in Vorbereitung sein. Eine gute Nachricht, denn ein solch anspruchsvoller und wichtiger Dichter sollte noch mehr Aufmerksamkeit beim Lesepublikum finden; und der Vergleich der verschiedenen Übersetzungen wird sicherlich zu weiteren interessanten Diskussionen führen. Ich bin jedenfalls gespannt.

Паул Целан: Избрани стихотворения, Gutenberg, Veliko Tarnovo 2019 (Übersetzerin Maria Slavcheva)

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-2020. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter