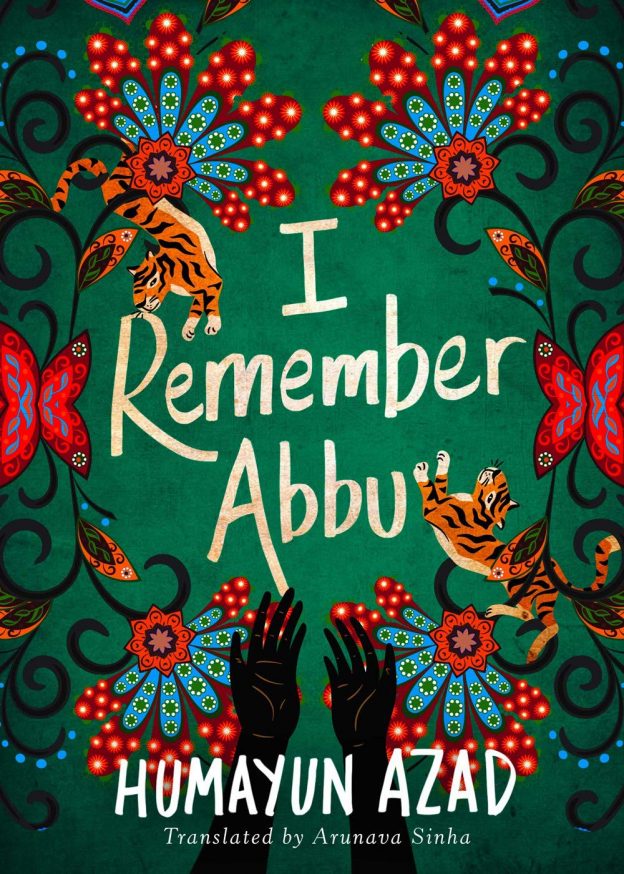

I Remember Abbu by Bangladeshi writer Humayun Azad is a short novel about a loving father-daughter relationship, but also a book about loss and memory.

The narrator, a girl or young adult woman remembers her early childhood, and especially her Abbu (father) and the special bond they shared. There is also an Ammu (mother), but in the light of the future events that are revealed later on in the book, the narrator is telling mainly her father’s story.

There is nothing spectacular in the first chapters of the novel; father, mother and daughter form an average family that obviously belongs to the educated middle class (the father teaches in University as we learn later on). In short chapters that are written from the perspective of a small child, we see how the girl learns to walk and to speak, how it sleeps in the same bed with her parents, how her father invents names and little stories for his daughter and so on. The first painful experience comes with the arrival of some kittens that are later thrown out again out of fear for the child’s health. The father, driven by a bad conscience, returns later to the place where he released the cats, but they are gone.

The averageness of the family and the experiences are underlined by the fact that there are only three protagonists (and a few passing figures without real importance for the novel), and none of them has a name. It is an archetypical small family, where the only child receives much attention and love from both her parents.

But there is a certain moment when things change. The father is absent more frequently from home, becomes less talkative and starts to get more serious and concerned about things that the child doesn’t understand. Only much later, when she is already grown up and reads her father’s diary from that period, things fall into place for the narrator and the reasons for her father’s change become clear.

Political tension is growing in the late 1960s and early 1970s in what was then known as East Pakistan and became later Bangladesh. The fight about the recognition of Bengali (Bangla) as a second official language in Pakistan, the non-recognition of the election results in Pakistan that would have made East Pakistan’s politician Mujibur Rahman President, the declaration of independence of Bangladesh, and the bloody genocidal war of Pakistan’s army in Bangladesh, it is all reflected in its consequences on the family in the novel. Abbu, as an intellectual and potential political leader has to hide from the army, the family flees to the village, on the way there they witness atrocities committed by the Pakistani army and finally Abbu leaves the family to join the underground fight against the oppressors.

From history books we know the result of the political struggle for freedom and political independence: Bangladesh became an internationally recognized independent country after much bloodshed and the military support of the neighbor India. Millions of people perished as a result of the fights and the starvation that followed. And while the victory over the demons (this is how Pakistan’s forces are called by Abbu) in this fight is welcomed by the people, Abbu’s family is waiting in vain for his return…

At a mere 123 pages, this is a small novel, written mostly in a rather simple language. The simplicity of the child’s thoughts, her struggle to understand why her beloved Abbu changed so much, and why he disappeared, are evoking strong emotions in the narrator, and also in the reader. The diary part, written by Abbu himself, is of course much more reflected and elaborated. It is indeed heartbreaking to see how historical events destroy the lives of otherwise perfectly happy families. But for the narrator, reading her Abbu’s diary may help her to come to terms with her tragic loss.

This was the first book by a contemporary Bengali writer I read. It was also the first book published by Amazon Crossing I read; the imprint used to be rather active for some years to get books from “smaller” languages translated into English. The translation by Arunava Sinha seems flawless.

The author Humayun Azad was a lifelong advocate of the Bengali language and one of the most important intellectuals in East Pakistan. His critical voice against radical Islamism and against the suppression of women made him a target of terrorists. In 2004, there was an assassination attempt of several men who stabbed him a few times in the neck and jaw. Against all odds, he survived; but some months later he died in Munich, where he was spending time as a researcher at the University of Munich.

Since I will be relocating to Dhaka soon, you can expect more reviews of South Asian, especially Bengali/Bangla literature in the future.

Humayun Azad: I Remember Abbu, translated by Arunava Sinha, Amazon Crossing, Seattle 2019

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-21. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter