The novel “The Price of Freedom” by the French-speaking author Matéo Maximoff recounts the life of a group of Roma in Moldova in the first half of the 19th century, at a time when this ethnic group was still living as slaves in what is today Romania. As the title of the book already indicates, the struggle for the freedom of the Roma – as shown by the example of the characters in the novel – is the central theme of the book.

Young Istvan, the main character of the book, works as a clerk and librarian in the court of the rich landowner Andrei. He owes this position, which is unusual for a Rom, to the fact that Andrei, who is ruling his estate as a mostly benevolent patriarch, recognized the intelligence of the young Istvan early on and promoted him. Istvan grew up together with Andrei’s sons of about the same age and thus, compared to the situation of his family and the other Roma who work for Andrei, achieved a “privileged” position. This, however, has no legal effect on his status as a slave and personal property of the landowner; as a slave, he is always at the mercy of his owner. This special position isolates him both from his own community, where on the one hand he is respected but also viewed with suspicion, and also from the community of free people with which he lives on a daily basis.

Another outsider in this environment is Yon, who is not only the landlord’s energetic right-hand man, but also his illegitimate son – a secret that is known to Istvan. Yon’s competent and energetic work distinguishes him from the legitimate sons of the landowner. While the Roma fear him as the powerful and sometimes ruthless representative of Andrei – he can impose severe punishment at any time -, Yon knows very well that he can never achieve a position that would be in line with his great energy and ambition; this position will be reserved for Andrei’s legitimate sons. The two outsiders Istvan and Yon have an occasionally conflict-ridden relationship, but one that is also based on mutual respect. Since they have known each other since childhood, a strange friendship, characterized at the same time by rivalry, has developed over the course of time. The role that both have to play as outstanding representatives of their respective social groups is simply too contradictory to get along without the tensions that become more and more apparent as the book progresses.

Maximoff chooses a clever introduction to his story: the book starts with the big market day in springtime. During this occasion, slaves are also sold and bought. Yon buys a group of Roma, including Lena, a girl that he obviously intends to turn into his lover. To protect Lena from Yon’s stalking, Istvan, who got Andrei’s blessing for this, gets engaged to Lena – which not only annoys Yon very much, but also fills Istvan’s lover Rayka with great jealousy. She had hoped that her relationship with Istvan would lead to marriage and sees her prospects threatened. Rayka’s jealousy is at the beginning of a fateful and dramatic chain of actions that culminate in the flight of Istvan, his family and a few other Roma; an escape that is of course not simply accepted by Andrei and his people, who suspect that Istvan murdered one of Andrei’s sons.

During their flight, the Roma group around Istvan faces an outlawed group of Roma who live in the remote mountains and who have realized their dream of a free life without oppressors. After initial reluctance, they accept Istvan and his group because of his honesty, courage and cleverness and let them join their community.

In the looming “showdown” between Yon – supported by the military, which is involved in the search for those who have fled – and Istvan and his Roma, a fight with great severity and brutality takes place, which will lead as a result to many victims on both sides. But violence is not the last word in this novel. In 1855, the political leader of the country, Alexander Ghika finally abolishes slavery in all of Romania (Moldova and Wallachia). And the story of Istvan comes to a resolution during a later court case that ties all the loose ends of the story together, giving it a last surprising twist. I don’t want to reveal more here in order not to spoil this very exciting story unnecessarily for readers.

I liked the book. It introduces the reader to the life of the Roma in the 19th century and I find it very embarrassing that although the slavery of the African Americans in the south of the USA is well known and explored, while at the same time, the fact that the Roma in Moldova and Wallachia were living in very similar conditions during the same period, is largely unknown in Europe and elsewhere. The book is shedding light on the plight of the Roma, and the reader has to be grateful to the author for this. The story itself is told with a lot of tempo and a feeling for dialogue, and even if not all characters are drawn without clichés, this story is definitely worth reading. It is also interesting that the author at least in passing mentions the fall in prices on the market for slaves; this is another parallel to slavery in the American South. Slavery disappeared in the end because it couldn’t survive in the changing economic and technical conditions.

The author, Matéo Maximoff, was born in Spain to a Kalderash Rom father from Russia – hence the Slavic family name – and a Manouche Sinto mother from France (she was a cousin of Django Reinhardt). At the age of eighteen or nineteen – his exact birthday is unknown – he moved to France with his family during the Spanish Civil War. Maximoff was the first one of his clan who had learned to read and write early on. While he was in prison – three people were killed in an argument within his clan, whereupon the police arrested indiscriminately everyone from his family – he began to write his first novel, which was later to be followed by ten more. After the end of World War II, Maximoff, who survived internment in a Nazi concentration camp himself but had lost many family members, began his successful career as the first Roma writer ever. Over several decades he was also an activist and fighter for the equality of his ethnic group in France. He also translated big parts of the Bible into the Kalderash Romanes language.

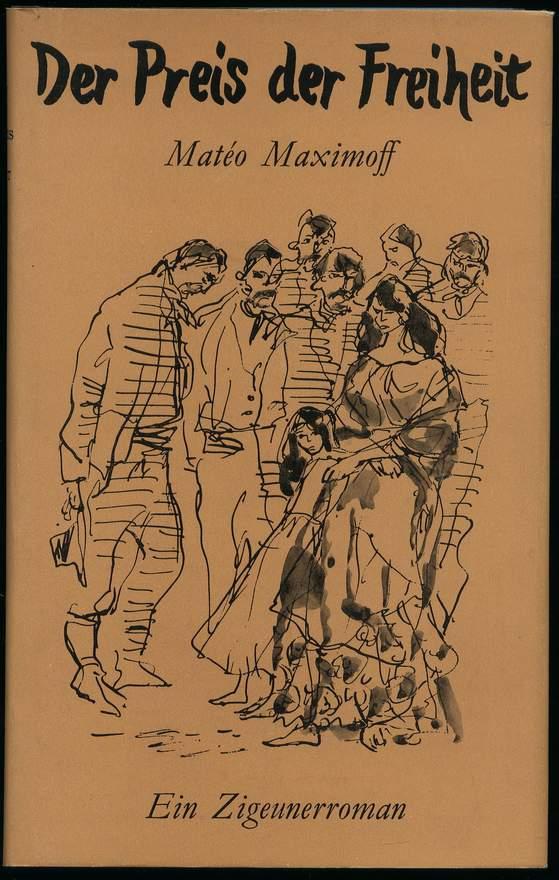

I read the book in the German translation that was published in 1955. It seems that none of his books are in print at this moment, neither in the French original, nor in English or German translation.

There is a very interesting award-winning Romanian film that also deals with Roma slavery: Aferim!. I can highly recommend the film; you can watch a trailer here.

Matéo Maximoff: Le prix de la liberté. Wallada, 1996; Der Preis der Freiheit. Morgarten Verlag Conzett & Huber, Zurich 1955 (tr. Bernhard Jolles)

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-21. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter