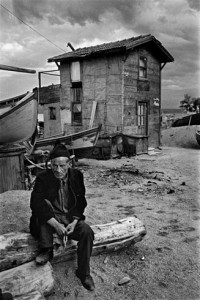

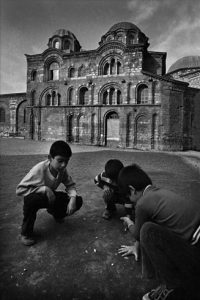

A scarecrow in the village of Zimzelen in the Rhodopes; a man reading a newspaper in front of some park benches in Ruse; an ultra-nationalist rally in Sofia; a Roma girl dancing with closed eyes in the village of Kovachevitsa; men playing chess in the park in front of Naroden Theater in Sofia; a man in a rakija distillery in a village near Karnobat; two elderly Pomak women in traditional dresses with a snow-covered peak of the Rhodopes in the background; a border fence at the Bulgarian-Turkish border near the village of Beleozen; a girl behind the bar of a self-service pub in the village of Chervenka; a beggar and his dog on Vitosha Street in Sofia; men in a village mosque; two old men in Sozopol at the Black Sea; an abandoned school in a village in the Strandzha mountains; the Jewish cemetery in Karnobat –

these are just some of the subjects of the photos in Anthony Georgieff’s new book The Bulgarians, recently published in a high-quality bi-lingual edition.

In the instructive foreword Georgi Lozanov points out the similarities of Georgieff’s anthropological photographic project with Robert Frank’s classical book The Americans. The Bulgarians shows a big variety of “average” individuals from different background, religion, ethnicity, age, gender, profession, social status, from urban areas as well as from remote villages, accompanied by photos that show human traces, graffiti, dilapidating buildings, or monuments of different eras, decaying or still fully revered. The element of the extraordinary moment, or of celebrity is carefully avoided in most cases (and when not, it is not with the aim to show celebrity, as is the case with the shot of a TV screen that shows the present Prime Minister, a photo that is reflecting the way most Bulgarians perceive politics). This, together with the careful composition of the work, make this – predominantly black and white – photo book a highly interesting statement regarding the identity of Bulgarians in the early 21st century.

While the parallels with Frank’s book are obvious, Lozanov points out also the differences which are particularly stunning when one compares photos of retired Americans with those of their Bulgarian peers:

“The former dress up in brightly coloured clothes, when their time for ‘well-deserved retirement’ comes, hang cameras around their necks, and start travelling the world. The latter (i,e. the retired Bulgarians – T.H.) put on dark clothes and headscarves, and sit on benches in front of their houses waiting for the world to pass them by. In The Bulgarians you will see Bulgarian grannies being passed by by the world.”

Not surprisingly, smiles are rare on the pages of The Bulgarians, but not completely missing. Georgieff has a sharp, but sympathetic eye – and for most people in Bulgaria, there is little reason to smile.

Two family photos from the private archive of the author open and end the photo sequence in the book. While the first one depicts a funeral in the family, approximately 90 years ago, the second one shows the author as an optimistic looking child. The comment the child wrote on the back of the photo made me smile, but you have to read it yourself…

Renowned journalist, photographer, and author Anthony Georgieff, the man behind Vagabond, the highly recommended English-language journal that publishes among other interesting articles about Bulgaria in every edition a story or an excerpt of a longer work by a contemporary Bulgarian author, has done an excellent job and this “anthropological roadtrip” will enrich everyone with a serious interest in Bulgaria and its people. It is also a photography book that may well be considered a classic in the years to come.

Georgieff told me after the book presentation I attended two days ago in Sofia that he is planning also a work related to Communist Bulgaria in the near future. I can say that I am looking forward to this work with great curiosity.

Anthony Georgieff: The Bulgarians. Preface by Georgi Lozanov, Vagabond Media, Sofia 2016

Some photos from the book you can find here.

The same publisher has produced some other equally interesting books that document Bulgaria’s cultural, historical, religious and ethnic diversity in English and Bulgarian, and that are illustrated with excellent photos as well. More information on these books you can find here.

#BulgarianLitMonth2016

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter