Incredible how fast one year has passed – another Women in Translation Month!

My modest contribution to Women in Translation Month is an overview regarding the books by female authors (or co-authors) I have reviewed, mentioned or from which I have translated texts (poetry) that I have published on this blog since last years’ Women in Translation Month:

Bozhana Apostolowa: Kreuzung ohne Wege

Boika Asiowa: Die unfruchtbare Witwe

Martina Baleva / Ulf Brunnbauer (Hg.): Batak kato mjasto na pametta / Batak als bulgarischer Erinnerungsort

Veza Canetti / Elias Canetti / Georges Canetti: “Dearest Georg!”

Veza Canetti: The Tortoises

Lea Cohen: Das Calderon-Imperium

Blaga Dimitrova: Forbidden Sea – Zabraneno more

Blaga Dimitrova: Scars

Kristin Dimitrova: A Visit to the Clockmaker

Kristin Dimitrova: Sabazios

Iglika Dionisieva: Déjà vu Hug

Tzvetanka Elenkova (ed.): At the End of the World

Tzvetanka Elenkova: The Seventh Gesture

Ludmila Filipova: The Parchment Maze

Sabine Fischer / Michael Davidis: Aus dem Hausrat eines Hofrats

Heike Gfereis: Autopsie Schiller

Mirela Ivanova: Versöhnung mit der Kälte

Ekaterina Josifova: Ratse

Kapka Kassabova: Street Without a Name

Gertrud Kolmar: A Jewish Mother from Berlin – Susanna

Gertrud Kolmar: Dark Soliloquy

Gertrud Kolmar: Das lyrische Werk

Gertrud Kolmar: My Gaze Is Turned Inward: Letters 1938-1943

Gertrud Kolmar: Worlds – Welten

Harper Lee: To Kill a Mockingbird

Sibylle Lewitscharoff: Apostoloff

Nada Mirkov-Bogdanovic / Milena Dordijevic: Serbian Literature in the First World War

Mary C. Neuburger: Balkan Smoke

Milena G. Nikolova: Kotkata na Schroedinger

Nicki Pawlow: Der bulgarische Arzt

Sabine Rewald: Balthus: Cats and Girls

Angelika Schrobsdorff: Die Reise nach Sofia

Angelika Schrobsdorff: Grandhotel Bulgaria

Tzveta Sofronieva: Gefangen im Licht

Albena Stambolova: Everything Happens as it Does

Maria Stankowa: Langeweile

Danila Stoianova: Memory of a Dream

Katerina Stoykova-Klemer (ed.): The Season of Delicate Hunger

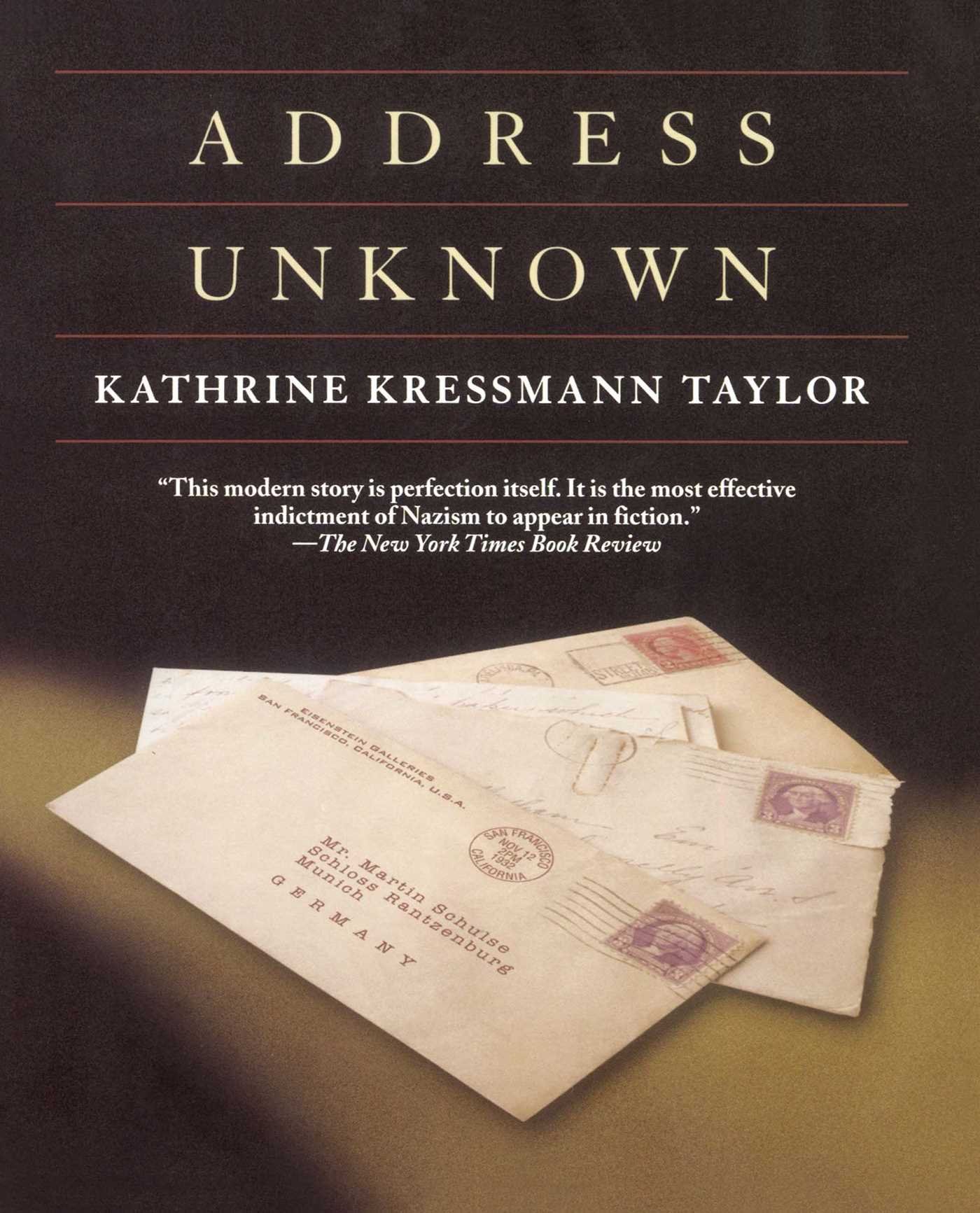

Kathrine Kressmann Taylor: Address Unknown

Dimana Trankova / Anthony Georgieff: A Guide to Jewish Bulgaria

Marguerite Youcenar: Coup de Grâce

Edda Ziegler / Michael Davidis: “Theuerste Schwester“. Christophine Reinwald, geb. Schiller

Rumjana Zacharieva: Transitvisum fürs Leben

Virginia Zaharieva: Nine Rabbits

Anna Zlatkova: fremde geografien

The Memoirs of Glückel from Hameln

What remarkable translated books by women have you read recently or are you reading right now?

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter