The story of Forty Steps by the Bangladeshi author Kazi Anis Ahmed (a.k.a. K Anis Ahmed – the name is in this form on the book cover and title page) begins with an end: Mr. Shikdar, a respected citizen of the sleepy provincial town of Jamshedpur somewhere in Bengal after the partition of India in 1947, has just been buried. Now he is waiting for the angels Munkar and Nakir, who, according to Koranic tradition, question the deceased about their lives and register the good and bad deeds and then decide if the departed will go to heaven or to hell – but not before the mourners have moved at least forty paces from the grave . As Mr. Shikdar counts the slowly receding steps in his grave, he lets his life go by once more in his mind…

How is it possible that a dead person can have such thoughts? Well, maybe he’s not really dead and after a faint he was quickly buried without a prior medical examination of the corpse – but why? Or is he – like Schrödinger’s cat – both alive and dead in his grave, at least until he has counted the forty steps? Or maybe we readers are just victims of a literary joke by the author?

Be that as it may, the reader takes part in Shikdar’s life confession, in the course of which we not only witness the unrealized dreams and disappointments of his life, but also get to know the most important people who determine his fate.

There is the Englishman Dawson, an unsuccessful art student, whom Shikdar befriends during the latter’s studies at medical school. Dawson arouses Shikdar’s interest in art. Later, Dawson tries to gain a foothold in his home country for a while, but returns disappointed – rejected by English society as an outsider who has “gone native” – back to Bengal to open a furniture business.

Then there is Molla, the nominal religious leader of the small town, who is a quite enterprising fellow and who finds in Shikdar an unexpected business partner. Shikdar “knows” a lot about documents, i.e. how to falsify sales contracts from real estate transactions well, so that land goes smoothly from the hands of the real owners to those of more capable people (= Molla and Shikdar) – a practice still a common practice in contemporary Bangladesh. To Shikdar’s defense it has to be added that the person with the criminal energy here is Molla, with Shikdar giving in reluctantly – because he is weak and loves to have a bit luxury in his life.

Then there is the beautiful Begum Shikdar, significantly younger than her husband and not averse to erotic adventures. When she finally gets pregnant, her blond child unfortunately dies during birth and is buried hurriedly at night almost without witnesses – with the exception of Molla, Shikdar’s partner in this suspicious enterprise as well. Dawson, on the other hand, is spending more and more time in the neighboring town, where he allegedly has an illegitimate daughter…

And then of course there is Mr. Shikdar, a good-natured person with no outstanding talents or particular energy, whose leanings for comfort and lack of resolve often stand in his way during his life. Small and large events such as the hustle and bustle of the fish sellers or the occasional senseless violence that flares up between Muslims and Hindus in the community are accepted with the same devotion to fate as something that has not changed in living memory and will not change in the future.

All in all, a rather uneventful life that the people we meet are leading and which is shown to the reader with humor and gentle irony. An example: Mr. Shikdar comes home from the big city without a diploma. But since there is no medical assistance in town, he is still often visited as a healer and asked for advice. For all sorts of actual and imagined ailments, he usually administers harmless medication, the sale of which ensures his livelihood; He also promotes birth control – but only until he takes on the part-time job of the ninety-year-old midwife, who has gone completely blind. After that, the issue of birth control loses all appeal for him …

The ease with which the author jumps back and forth between realism and fantasy in this narrative is amazing. As relentlessly as the obvious weaknesses of their main characters are shown, however ridiculous they often appear – they are portrayed with sympathy and warmth. The trivial and the fantastic, the real and the sublime, in this masterful story they are interwoven in the most beautiful way.

It is also worth mentioning that the story was written in English. Bangladeshi writers write mainly in English and Bengali (Bangla); however, texts in English often differ from texts in Bengali in regards of their sociocultural context: texts written in English tend to deal more with the educated and relatively wealthy class – the common people and especially the rural population often only appear marginally. Kazi Anis Ahmed, together with several other authors, has made a significant contribution to breaking up this traditional dichotomy with his literary work.

In recent years there has been a flourishing of English-language literary publications in Bangladesh – both in the original and in translations from Bengali. Magazines such as Six Seasons Review, the literature pages of English-language daily newspapers such as The Daily Star and New Age and the publications of the publishers Bengal Lights Books, Bengal Publications and Daily Star Books, as well as Dhaka Lit Fest, an annual international literature festival, are an expression of this development.

A word about the author: Kazi Anis Ahmed was born in 1970 in Dhaka. Forty Steps was originally published in 2001 in Minnesota Review to great critical acclaim. The World In My Hands, a collection of stories, followed in 2013, and in 2014, he published his first novel, Good Night, Mr. Kissinger. Apart from regularly contributing to international media such as The Guardian, TIME or The New York Times, he co-curated also a special Granta edition on Bangladesh. Ahmed is the co-founder of the University of Liberal Arts in Dhaka, as well as the publisher of the newspaper Dhaka Tribune and other media outlets. He is the co-director of the annual Dhaka LitFest, as well as the director of Gemcom, a group of businesses founded by his father. He is to my knowledge the only writer who owns a successful organic tea estate – Kazi Tea is exported to many countries.

The book edition I used is bilingual. The English original text is followed by the Bengali translation by Manabendra Bandyopadhyay – the typeface of the Bangla version alone is a pleasure! A nice initiative by Bengal Lights Books to make this masterful narrative accessible to those Bengali speakers who do not speak good English.

In summary: this story is a small gem that I like very much!

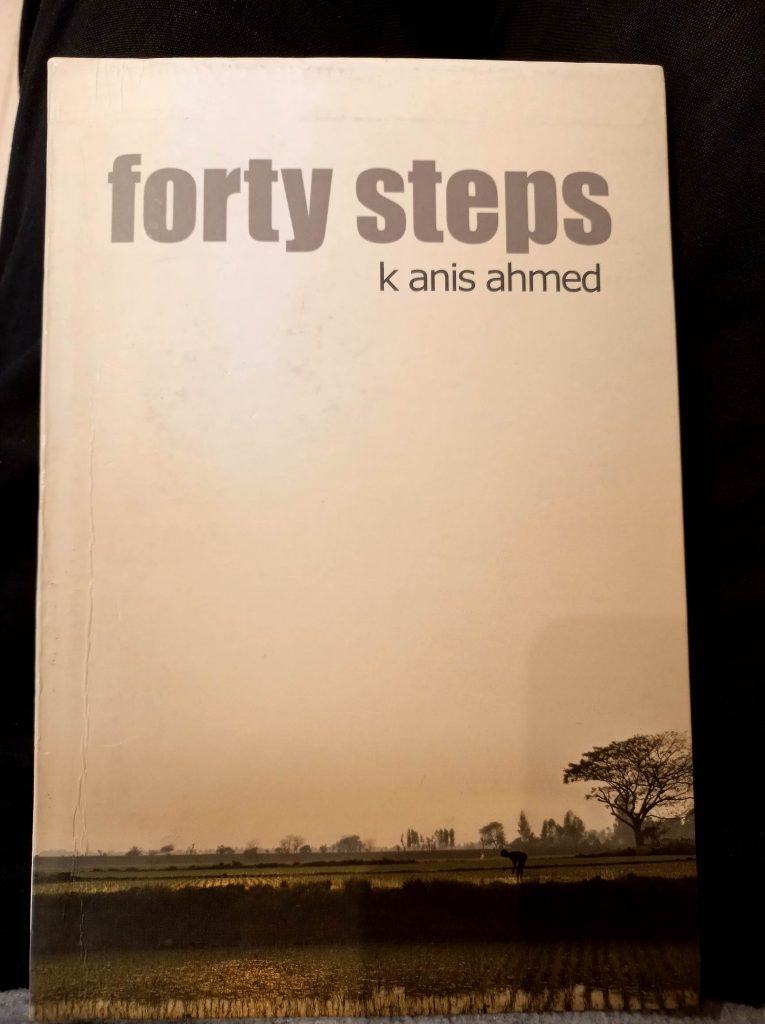

K Anis Ahmed: Forty Steps, Bengal Lights Books, Dhaka 2014 (bi-lingual edition English/Bengali, tr. Manabendra Bandyopadhyay)

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-22. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter