© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Monthly Archives: March 2016

A disturbing fairy tale

The by far most disturbing fairy tale I ever came across in my life, and also one of the most disturbing literary texts I ever encountered goes like this:

“Once upon a time there was a poor little child and had no father and no mother all dead and was no-one left in the whole world. All dead, and it went off, crying day and night. And since on earth there was no-one left it wanted to go up to heaven where the moon looked at it so kindly and when it got finally to the moon it was a lump of rotten wood and so it went to the sun and when it got to the sun it was a withered-up sunflower. And when it got to the stars they were little spangled midges stuck there, like the ones shrikes stick on sloes and when it wanted to go back to the earth, the earth was an overturned pisspot and ‘t was all alone, and it sat down and cried, and it is still sitting there and is all alone.”

(„Es war einmal ein arm Kind und hat kei Vater und keine Mutter war Alles tot und war Niemand mehr auf der Welt. Alles tot, und es ist hingangen und hat gerrt Tag und Nacht. Und wie auf der Erd Niemand mehr war, wollt’s in Himmel gehn, und der Mond guckt es so freundlich an und wie’s endlich zum Mond kam, war’s ein Stück faul Holz und da ist es zur Sonn gangen und wie’s zur Sonn kam, war’s ein verwelkt Sonneblum. Und wie’s zu den Sterne kam, warn’s klei golde Mücken, die warn angesteckt wie der Neuntöter sie auf die Schlehe steckt und wie’s wieder auf die Erd wollt, war die Erd ein umgestürzter Hafen und war ganz allein und da hat sich’s hingesetzt und gerrt, und da sitzt’ es noch und ist ganz allein.“)

Georg Büchner, the author of the enigmatic and unforgettable play Woyczek from which this short fairy tale is taken, lets the grandmother tell this tale to the children that are present. The grandmother speaks in a slightly archaic and dialect-flavoured language which adds to the “gothic” effect. This is not the place to analyse the role of this dark tale within the play but it still gives probably everyone a feeling of utter hopelessness. It is a post-apocalyptic fairy tale, a text without any hope or consolation – and probably a very appropriate text for the situation of mankind today -; the powerful language of Georg Büchner has an incredible effect on the reader, especially when you can read the German original.

In his short life (he died at the age of 23), he created a few works that stand out not only in German literature. His Lenz is for me the best German story and it still blows me away every time I read it. The same goes for his plays Woyczek, Danton’s Death, and Leonce and Lena, or his revolutionary pamphlet – co-authored with Friedrich Ludwig Weidig – Der Hessische Landbote (The Hessian Courier) with the famous slogan “Peace to the shacks! War to the palaces!” („Friede den Hütten! Krieg den Palästen!“)

I will for sure come back to this extraordinary author. If you have an opportunity to find an edition of his Collected Works, get and read it. You won’t regret it.

Büchner’s works have not only been an inspiration for many authors – the most prestigeous German literary award is named in honour of this man who was once a young refugee wanted by the police of his home country with an arrest warrant because of his fight for a democratic and more free society -, also many composers, film directors, and performance artists take inspiration from him. Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck, Werner Herzog’s movie Woyczek (with Klaus Kinski), and Tom Waits’s song Children’s Story from the album Orphans come to mind. The lyrics of that song: the text of the fairy tale quoted above (in a different translation).

Georg Büchner’s early death was without doubt one of the biggest losses for the world of literature, a real tragedy. His small number of works show an accomplished genius already at a very young age.

Georg Büchner, Complete Plays, Lenz and Other Writings, translated by John Reddick, Penguin Classics, 1993

The translation from German in this blog post is by Thomas Hübner.

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Lake Como

Residency programs are an important part of the working life of many authors today. They provide for a limited time, maybe a few weeks, a month, or a little bit longer a place in an interesting surrounding, suited to the specific requirements of authors, and frequently they come with a certain sum of money plus free board and plenty of opportunities to socialize with other people working on projects in the making in their respective field – other authors, artists, scientists. In the best case, residency programs provide an opportunity for an author to focus on his/her work, to write or finish a manuscript with which he/she has struggled since a long time and also to collect and exchange new ideas for new projects. Participating in such a program means that as an author you have for this limited time not to think about anything else than your work, particularly not about money. Everything is well taken care of by the host.

Contrary to what you could expect, the central role of residency programs for many modern authors is not reflected in the literary output of most of these authors. Very rarely – at least this is my impression – are works of fiction dedicated to experiences that authors make with such programs. There are exceptions of course, such as Lake Como by the Serbian novelist Srdjan Valjarevic, the book about which I am writing here.

Nothing spectacular happens in this book: the narrator, a Serbian author that has for sure many similarities with the author of Lake Como, wins a Rockefeller scholarship that comes with an invitation to spend one month in the lovely Villa Maranese in Bellagio near Lake Como. A good opportunity to finish a novel (which he has indeed no intention to write at all), and also to leave behind a flat in Belgrade with a leaking roof, some financial debts and other personal problems, and a more and more difficult situation for intellectuals that are not in line with the official ultra-nationalist Serbian politics and its consequences. It is the end of the 1990s and the armed Kosovo conflict is in its early stages.

During his stay in the Villa, the author meets all kind of other Rockefeller fellows from all over the world busy with all kind of projects. People talk, socialize, eat and drink, gossip, work a bit or rather not, a composer gives some house concerts. The author feels like an outsider because of his age (he is by far the youngest in the Villa), his origin, his interests and even his clothes (he only reluctantly gets used to wearing a tie, which is strongly recommended in the Villa), not to talk about his drinking and smoking habits. (My apologies when I mention the drinking so frequently, but there isn’t probably a single page in the book when the narrator doesn’t have a drink.)

An additional predicament is that the protagonist has to lie to almost everyone about his work: since he is known to be a novelist, people want to know how the work with the novel is going and instead of telling them that he is just enjoying the time doing nothing – except eating, drinking, sleeping, and the occasional walk to the village or a nearby hill – the author/narrator is making up things related to the non-existing novel. But the not existing work in progress is at least a good excuse to get away from activities in which he doesn’t want to participate.

Apart from that, he explores the village, has a short fling with a female guest of the Villa, makes friends with a friendly bar owner, as well as with Alda, a young charming girl working in another bar with whom he is communicating in a mixture of English, Italian, and drawings. He makes some friends at the Villa as well, particularly the waiters that provide a never-ending stream of wine, whiskey and other alcohol, but that are also a valuable source of information about the place. With Mr Sommerman, a holocaust survivor and retired literature professor and his wife, he is developing a friendship that will probably last even after he leaves the Villa when the time is over. And the meeting with another guest who visited once the island of Korcula in what is now Croatia brings back long hidden memories to the author because this place had a particular importance in his earlier life.

Of course, this book reminded me more than a bit of The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann. The villa is on a hill – ironically called “Tragedy” – not a real mountain, but the setting is very idyllic (Bellagio is already part of the Mediterranean world, but with a view to the snow-covered mountains of the Alps), like a temporary paradise isolated from the rest of the world with all its problems. Valjarevic has a very good ability to characterize people and it seems he talks of his own experience, so vividly retold are many episodes, frequently with a slightly detached irony. There are also beautiful pages where he is describing the nature at Lake Como. And also small observations like what he is writing about the transistor radio, were really interesting to read for me. The visit of Alda and her family on the hill – for some strange reason, most people from the village have never visited the Villa; so near and yet so far are these worlds from each other usually – is a highlight of the book.

A little bit on the downside though is the fact that a considerable part of the novel is a repetitive mentioning of drinking, eating and sleeping habits of the narrator. Not a single drink goes unnoticed, and after a while I was really not so much interested any more in what the narrator did to his liver. This feeling of repetitiveness is even strengthened by the author’s habit to write many short sentences starting with “I”. I did this. I did that. I did this. Then I did that. Ok, most sentences are a bit longer, but the style was for me in many parts of the book not very attractive. Although the narrator refers to Robert Walser, Robert Musil, Walter Benjamin as favourite authors, the style of the novel is more like Hemingway – and that is not at all a compliment in my opinion. These issues somehow prevented me from enjoying this book as much as I wanted to like it.

Srdjan Valjarevic is an interesting and very talented author. With some more editing, Lake Como could have been an excellent novel.

Geopoetika, a publishing house in Belgrade, has published a series of books by contemporary Serbian authors in English. I can recommend you this series if you want to get to know interesting literature from Serbia.

Srdjan Valjarevic: Lake Como, translated by Alice Copple-Tosic, Geopoetika, Belgrade 2009

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

“We can always call them Bulgarians”

“…columnist Wilella Waldorf in the New York Post, September 17, 1937 about the play Wise Tomorrow:It has been whispered the theme has a touch of Lesbianism about it, which sounds a little odd when you consider that the Warners, presumably, have in mind a picture version eventually. However, as Samuel Goldwyn or somebody once said, “We can always call them Bulgarians.””

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

News from Retardistan (4)

A bookstore in Sofia – the same about which I reported recently, the one which advertised Hitler’s My Struggle as “Hit” and put it in such a tasteful manner on a table beside á book of holocaust survivor Primo Levi:

To my surprise, Hitler’s book has finally disappeared from the prominently placed table (Primo Levi too). Has someone read my posting and realized that a book that is advertising the extermination of the Jews, published by a Nazi publishing house and with a portrait of Hitler on the cover that was an official portrait supposed to glorify him and that is obviously targeting an audience of raging anti-Semites and Nazis should not be sold in an establishment that is selling books? Unfortunately not!

My Struggle has not disappeared, but has moved to an even more prominent place: now you see this vile rag of a book in several copies almost jumping in your face when you enter this bookstore, placed on a display rack which every person that enters must notice.

And it goes without saying that the place previously occupied by My Struggle has found a “worthy” placeholder: Henry Ford’s The International Jew in Bulgarian edition, one of the main “inspirations” of Hitler and not much less radical regarding the “solution” of the “Jewish problem” as My Struggle.

Let me guess: when I visit this “establishment” (I avoid the word bookshop) next time, I will probably see Ford replaced by the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion“? Or Celine’s “Bagatelles pour un massacre“? Or the “Leuchter Report“? And in the children’s section maybe an edition of pornographic/anti-Semitic pictures from Julius Streicher’s “Der Stürmer”, labeled as usually with “Hit” and maybe in this case with the additional tasteful sticker “great educational value!”, preferably placed beside the The Diary of Anne Frank?.

Retardistan is a place where nice books that spread certain “values” even in the last household are held in great esteem, a place where people of a certain “culture” have it very easy to find what is arousing their interest and honestly, isn’t it great to find books that promote mass murder, systematic extermination of people and extreme racial hatred without any effort? Hail Retardistan!

(Irony button “off”)

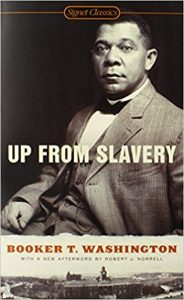

Up from Slavery

The autobiography of Booker T. Washington Up from Slavery is an interesting book for various reasons. It belongs to the small group of works written by black men in the United States that were born as slaves and who later gave witness regarding their lives as slaves and thereafter (i.e. after the end of the Civil War, when slavery was officially abolished in the South). Other works of this genre include Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave, and Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

But apart from being a very interesting document in itself, the book is also interesting until today because Washington was the first black leader in the U.S. to address big audiences in the North and the South, black and white alike, a man with a mission – he founded the Tuskegee Institute (today Tuskegee University) in 1881, the first school in which black teachers were trained and students had a chance to learn also professional skills that would prove to be the economic basis for the further social development of the black population in the South.

Washington was probably born in 1856, the exact date and month are not known. He grew up on a farm in Virginia in very basic conditions although the slave holding family seems to have treated their “property” comparatively well. The chapters in which Washington describes his childhood on the farm and the time after the end of the Civil War, when the family moved to West Virginia, are very touching.

Washington, the son of a white farmer whom he didn’t know and who didn’t care the least for his offspring, had from early childhood on the wish to get an education, to learn how to read and write and lift himself up from the conditions in which he and the other black people in the South lived. A big part of the book deals with the struggle of young Washington to achieve this goal. For years, Washington had to go through many hardships and worked in very difficult conditions as a salt miner and in other menial jobs in order to earn the required money to pay the tuition fees at school. When he finally made it to the Hampton Institute, a progressive school that gave an opportunity to many black people to get an education, Washington didn’t miss this chance and put all his energy in graduating there.

What follows is a story of hard work for a good cause: after graduating from Hampton Institute, Washington was assigned to become school principal in the newly founded Tuskegee Teachers’ School at the age of 25. He secured the support of the local people, but also of many donors in the South and the North as well (including former slave owners) by convincing them with results. The students in Tuskegee earned from the very beginning their own money in the workshops of the Institute, where they learned various professions, they erected the buildings of the fast growing school all by themselves and provided the regional market with various products in demand.

A person who makes himself useful and who is able to do something well and better than others will in the end be accepted by any community – this is the way how Washington wanted to achieve a true emancipation. Once most of the black people have a regular work and a profession or trade in which they can make a living, the relations between the races will improve as much as to make the racial prejudices and discrimination disappear – we should keep in mind that Washington published his autobiography when lynching was an everyday occurrence in most states of the South, and when more and more Southern States disfranchised the black population and withdrew the voting right from them, and when the Ku Kux Klan was at the height of its power and influence.

Washington’s approach was of course in a way naive: racism doesn’t simply disappear just because those against whom the racists discriminate (or worse) behave well, use a toothbrush – Washington is quite special about the use of the toothbrush and personal hygiene in general – and have a regular employment or learned a trade or profession that is useful to the community in which they live. On the other hand, Washington’s optimism, his clear vision and his obvious great energy and devotion to a project that really improved the lives of many people, together with his apparent skills as an orator, and his personal charm and modesty – this all opened the hearts and the purses of many people, including people like Rockefeller, Eastman or Carnegie. In the end, Washington advised Presidents, was the first black man to be awarded a honorary degree from Harvard and was received in many places like a rock star would be today.

It is quite interesting that the biggest opposition to Washington’s educational program didn’t come from white Southerners but from a faction of Washington’s “own people” in the North. Especially after his famous Atlanta Exposition Address of 1895 in which he became visible as the unchallenged leader of the black people in America, he was attacked by a faction under the leadership of W.E.B DuBois.

DuBois, who graduated in Berlin and became later the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, was initially supporting Washington, but he soon changed his opinion. According to DuBois and his supporters, Washington was too soft in his stance against violations of Civil Rights, and also his preference of industrial education over the classical liberal arts was very much to the disliking of DuBois who believed that only an elite of men educated in the liberal arts – supposedly under DuBois’ leadership – would be able to achieve social progress. It was a clash of characters from different backgrounds and very different temperaments: here the Southern man whose own education was limited as a result of his difficult life circumstances, a man with a hands-on approach to things who believes that only by self-improvement, hard work and an understanding for what is possible in the moment, the Negro race can be uplifted in the long run; on the other side, the urban, well-educated Northerner, more a politician than an educator who aspired to be the political leader of the Negro race.

As a result, Washington and DuBois had a rather complicated relationship – and while Washington is not in any way saying a bad word about his opponent in his autobiography directly, it is quite obvious to whom he is referring when he mentions a rather ridiculous example of an “educated” Negro early in his book, as someone with

“high hat, imitation gold eye-glasses, a showy walking-stick, kid gloves, fancy boots, and what not…”

In general, the autobiography gives comparatively little away about Washington’s private life. He was obviously quite a family man and seemed to have suffered at times from phases of longer separation from his wife and three children due to his extensive travelling. He lost two wives very early, but in the book he keeps his private feelings private and is not talking in detail about his grief. Whenever anyone supported him he mentions it in the book – understandable when we are aware that it was also meant as an instrument in his fundraising campaigns for Tuskegee. A previous autobiographical book published for a black audience was more critical regarding certain aspects of the life of the black community in the South and mentioned also some particular cruel examples of treatment of slaves by white slave holders, but Up to Slavery is clearly written for a white audience and possible donors; therefore these examples are omitted in the reviewed book.

All in all, the Booker T. Washington we get to know in this book was a humble and very energetic man, who achieved probably more in terms of improvement of the living conditions of the black people in the South than anyone else before or after him. That he championed industrial (i.e. vocational) training over academic training in the liberal arts, shows a much greater sense of realism than most other self-proclaimed leaders at his or later times showed, and the experiences of Tuskegee Institute can be still considered today as a good practice in the context of developing countries and communities.

Booker T. Washington: Up from Slavery, Signet Classics, New York 2010

PS: The expressions “black people” or “Negro race” are expressions used in Washington’s book.

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Tokyo Decadence

The protagonists in Ryu Murakami’s collection of 15 short stories Tokyo Decadence are not your average salarymen and housewives you would probably expect from a contemporary Japanese author.

The stories, competently translated by Ralph McCarthy as it seems (I don’t speak Japanese and can judge only from the language of the translation), are taken from five story collections originally published between 1986 and 2003.

They are depicting mainly the lives of Tokyoites that live outside the “average” world of offices of big corporations. The men are film directors, novelists, university drop-outs, painters, musicians, petty drug dealers, waiters, or truck drivers, the women frequently single mothers, hostesses and call girls and they are in all their weirdness not so different from “us” average people: they are looking for love and friendship, for a way out of their unhappiness and misery, and for something that is missing in their lives – or in Japanese society in general; hence their fascination with baseball (in the first four stories, taken from Run, Takahashi!), cinema (in the three stories from Ryu’s Cinematheque), or Cuba and its music (in the four stories taken from Swans). And when they can’t find any of these things they are in a more or less conscious way longing for, there is still enough left to fill in the gaps and the emptiness: sex (lots of it!), drugs, and the joyless joys of consumerism (as in one of the strongest stories of the book, Topaz).

Tokyo Decadence could be a depressing read with all these drifters, hoodlums, prostitutes, drug addicts and women on the verge of a nervous breakdown or beyond; the fact that Ryu Murakami was hailed by some media as an author in the mould of Bret Easton Ellis or Chuck Palahniuk seemed to suggest that I was to expect a book I would most probably not really enjoy very much. But it turned out that this book was a pleasant surprise.

Ryu Murakami knows the milieu about which he is writing obviously very well; he is a TV host and a film director and also a producer of Cuban music; therefore his descriptions of the world of media or about Cuban music that are central to several stories feel absolutely authentic. As a film director and script writer he knows also how to write gripping dialogues. They are frequently very interesting because they reveal the real character of most protagonists. In several of the stories we get to know a character as narrator of the story before in the next story, told by another narrator, the main protagonist of the previous story is depicted in a very different way. Although each story is a stand-alone story, the frequent links between the individual stories of each collection give sometimes a feeling as if we are reading a novel or novella written from the standpoint of different narrators. And when I said in a recent review of a Colum McCann novel that that author obviously cannot create interesting female characters, the opposite is true of Ryu Murakami. Several of the narrators and main characters in the stories are women, and Murakami shows great empathy in describing them in all their humanity.

Another element that I must mention here and that adds to the flavour of this story collection is the humor in most of the stories. The way how the unemployed macho truck driver in It All Started Just About a Year and a Half Ago finds his true – and more than surprising – vocation as a male transvestite hostess in a gay bar; and how his daughter finds out the truth about it: it is a hilariously funny story. Or when in The Last Picture Show the young narrator who was just evicted from his home starts to collect hydrangea leaves at night with a yakuza from the neighbourhood (dried and rolled they smell like weed); the whole “drug” selling is more like a prank of two kids. At the same time Murakami is revealing the soft side of the young yakuza who starts to shed tears when he is watching the movie The Last Picture Show in a cinema with his new acquaintance. This moment seems also to be the beginning of a friendship between these two young men.

There is hope in many of the stories for the protagonists that their life will change one day. One of them really makes it to Cuba. And in the final story At the Airport when we are left guessing as readers until the last paragraph if Saito, the regular costumer of the sex worker who is telling us her story, and who fell in love with her will really turn up to bring her to a place where she can pursue the training for the profession she really wanted to learn since a long time, the narrator is watching an old couple waiting nearby: he is having a cigarette in the smoking area, while she is folding the paper wrappers of some chocolate she is eating. When the old man is coming back, his wife leaves him her seat. Getting old together is maybe the best that life has in stock for some of us, and while watching the old couple, the narrator seems to realize that this is also something she could aim at with Saito – who is turning up just in time at the last moment. A hopeful end of this story and the story collection I truly enjoyed.

Ryu Murakami – not related to Haruki Murakami – is author of forty novels, a dozen short story books, several collections of essays and picture books, and also director of five feature films. Tokyo Decadence is an excellent opportunity to discover one of the best and most prolific Japanese contemporary authors. Highly recommended!

Ryu Murakami: Tokyo Decadence, translated by Ralph McCarthy, Kurodahan Press, Fukuoka 2016

Thanks to Kurodahan Press for the Advance Review Copy.

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

“Ferrante Fever” – based on literary merit or hype?

I don’t know why but I am in an inquisitive mood these days – again I would like to ask my readers for an opinion or a feed-back.

The author “Elena Ferrante” is on the Man Booker International Longlist this year, which some of my blogger colleagues cover in detail. Check their reviews out, there are some great books on the list again.

Maybe it is just me, but I am a bit allergic against authors that are subject of a media hype. I am not inclined to read any books by Knausgard or Houellebecq any time soon, and I am afraid that the same goes for Ferrante, who keeps her/his identity a secret – thus creating an even bigger interest in her/him (gossip of usually well-informed insiders hints at a male author behind the pseudonym, which would render most comments about her feminism and background rather ridiculous; indeed a lot of the reviews focus on the personality of the author – about which we know absolutely nothing for sure, except for those bits we are told to believe, something I find highly problematic. Media shyness of the author or very clever marketing?).

I cannot say anything about the quality of the Ferrante books so far – as you see from my previous remarks, I am until now immune against the “Ferrante Fever”. I am not a friend of such deliberate obfuscations, and will read these books probably a bit later, when the hype has a bit calmed down and I don’t have the impression to be subject of a media campaign and collective frenzy.

Now I have a question for you, dear readers:

Did you read recently anything by “Elena Ferrante”? Is she(?) really as brilliant as almost everyone tells me or is this article in Commentary closer to the truth?

What is your opinion?

And, if you like, another question:

How do you approach “hyped” authors (like Knausgard or Houellebecq)? How do you prevent yourself from being influenced in your judgement regarding the literary merits of their books by the noise of the media around such authors?

Looking forward to your opinions!

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Three Books Only

Imagine you would be allowed to possess only three books – which three books would that be? And why these three?

I am looking forward to your responses! (My own answers will follow later.)

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Child of God

The novels of Cormac McCarthy are not exactly cheerful, uplifting books – in the contrary! This author is exploring human loneliness and isolation, depravation, and extreme violence in his work. The subject matter that leaves little to no space for any hope, consolation or redemption contrasts with a prose that is sparse but frequently very poetic. As a reader, I therefore feel usually quite wrought out after I finished one of his books, but at the same time I have the impression that I read something very remarkable and even beautiful. Very few authors leave the reader with such contradicting feelings.

My latest try with a McCarthy book was Child of God, his third novel and published before his devastating masterpieces Blood Meridian, All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, and The Road. And it is again confirming what I said in the above paragraph.

Lester Ballard, the main character, grows up in a small town in East Tennessee (the region in which McCarthy grew up) in the 1960s. Although his family seems to have lived in the area for generations – his grandfather was obviously a local Ku Klux Klan leader, and his father committed suicide by hanging himself – the boy is socially rather isolated. Already during his childhood he shows a violent, sociopathic behavior. After he loses his small farm and serving a prison sentence because he is threatening potential buyers of his former property with his rifle, he returns to his home region. He starts to live as a squatter in a dilapidated cabin, lives on stolen corn or squirrels and other prey he is shooting, and is considered as at least half crazy by the people in his home town.

Ballard is shown as practically unable to lead a normal conversation or to interact adequately with others. A conversation between Ballard and a smith who is sharpening an old axe for him is almost comical, but it is Ballard’s complete lack of ability to make a normal contact with women, that will have disastrous consequences for him.

The remainder of the book shows how the main character sinks deeper and deeper in isolation, degradation, even perversion. The social degradation and decline corresponds with a moral one and even a physical one: from squatter to cave dweller to prisoner; from voyeur to necrophiliac to serial killer; from healthy young man to mutilated prisoner to dissected corpse – this is the path Lester Ballard is going. And yet, he is

“A child of God much like yourself perhaps.”

Although the main character in this book is not a man most of us would be keen to meet, McCarthy is describing him with sympathy and understanding. If Ballard would have ever had a positive experience with others, if he had got as a child at least a little bit human warmth and support, he might very probably never turned out to be the person he became.

McCarthy is also a compassionate storyteller. The men who threaten to lynch the already crippled Ballard if he is not leading them to the corpses of his alleged victims, are full of blood lust and sadistic pleasure in their (self-)righteous endeavor, and as a reader we rejoice probably quite a bit when Ballard succeeds in escaping (temporarily) his tormentors.

The author is using different perspectives – some chapters are told from the viewpoint of neighbors of Ballard – and he is using spoken language for the dialogues which are given without quotation marks, a method that takes a little bit time to get used to as a reader.

What is it with Cormac McCarthy and the women? I cannot recall any remarkable female character in his books (at least the ones I read). Also in Child of God, the women are marginal figures, mainly victims of men. Not that he is particularly misogynistic, but this virtual absence or marginal role of women in his works is rather strange and I have no real explanation for it.

It would be not true to say that I have enjoyed this book. Too unpleasant, violent and full of graphic descriptions of human depravity is this novel. It is not McCarthy’s best book, but still an important step on the way to the mature masterpieces of his later years.

Cormac McCarthy: Child of God, Picador 2009 (originally published 1973)

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter