Dua lembar baju, celana, 3 celana dalam, dan handuk kecil kumasukkan

dalam tas. Lewat pintu belakang aku keluar, satpamku juga tertidur dekat

dengan kurungan herder. Tetapi terlelap.

Anakku, istriku kalau mau ketemu dengan aku tontonlah sirkus keliling.

Ich legte zwei Hemden, ein Paar Hosen, drei Unterhosen und ein kleines Handtuch in meine Tasche. Ich ging durch die Hintertür hinaus. Mein Wachmann befand sich neben dem Zwinger mit dem Schäferhund. Beide schliefen. Mein Sohn, meine Frau, wenn ihr mich sehen wollt, kommt und schaut euch die Zirkusvorstellung an.

—————————————————————————————————-

Dasar aku memang klepto, aku di kamar kecil Kereta Api (Train Urinoir) dan aku mencuri papan yang tertulis “Pergunakanlah hanya waktu kereta jalan.” Tidak berhasil karena pecah, bautnya terlalu kencang, BAJINGAN!!

Ich bin wirklich ein Kleptomane, ich war im Zugurinal und stahl das Schild auf dem steht „Nur benutzen wenn der Zug fährt.“ Es ging schief, denn es zerbrach, der Bolzen saß zu fest. BASTARD!!

—————————————————————————————————-

Telpon berdering.

“Halo, siapa?”

“Selli mas!”

“Selli?!”

Bekas pacarku dulu sekali, waktu aku masih ingusan dan pemalu banget.

Pegang jarinya saja sudah gemetar, ngomong juga jarang, jadi surat-suratan

terus.

“Berapa anakmu sekarang Sell?”

“Dua mas, cewek-cowok”

“Suamimu dimana?”

Dia ngomong lagi ngebor minyak di Riau. Kami janjian bertemu, dua hari

lagi. Di tengah hujan lebat, di bawah beringi, kutiduri ia dalam mobilku.

Aku tidak pemalu lagi.

Das Telefon klingelte.

„Hallo, wer ist dran?“

„Hier ist Selli!“

„Selli?!“

Sie war meine Freundin als ich noch ganz jung und schüchtern war.

Zu jener Zeit zitterte ich sogar, wenn ich nur ihre Hand hielt. Wir sprachen kaum jemals miteinander, aber wir schickten uns lange Zeit Briefe.

„Wie viele Kinder hast du jetzt, Sell?“

„Zwei, ein Mädchen und einen Jungen.“

„Wo steckt dein Mann?“

Sie sagte, ihr Mann wäre in Riau beim Ölbohren. Wir verabredeten uns für den übernächsten Tag. Im strömenden Regen, unter einem Banyan-Baum, fickte ich sie in meinem Auto.

Ich war nicht mehr schüchtern.

—————————————————————————————————-

Anjing hitam tak tau apa yang harus dia perbuat ketika dilihat tuannya

mencari-cari tali, mengikatnya di kusen pintu dan meletakkan kursi rendah di

bawahnya.

Der schwarze Hund wusste nicht, was er tun sollte als er sah, dass sein Herrchen nach einem Seil suchte, es dann am Türrahmen festband und einen Stuhl darunter stellte.

—————————————————————————————————-

Nahkodanya kapal Nuh terlalu banyak minum Rum. Sebuah ombak besar

datang menghantam dan langsung tenggelam. Nabi Nuh tidak bisa berenang

dan semua binatang yang dikumpulkannya mati. Hanya sepasang Gagak

yang sempat menyelamatkan diri.

Mereka terbang dan mencari sarang. Beranak pinak, anak cucunya ada

yang kawin sama ikan, gurita, kerang, ubur-ubur, penyu, dan kitalah

keturunannya.

Der Kapitän von Noahs Arche trank zu viel Rum. Eine gewaltige Welle krachte ins Schiff und es sank sofort. Noah konnte nicht schwimmen und alle Tiere an Bord der Arche wurden getötet. Nur ein Krähenpaar hatte genug Zeit zu fliehen.

Sie flogen davon und suchten nach einem Nistplatz. Dann brüteten sie; einige ihrer Kinder und Enkel heirateten Fische, Tintenfische, Austern, Quallen, Schildkröten, und wir sind ihre Nachfahren.

Aus dem Indonesischen übersetzt von Thomas Hübner

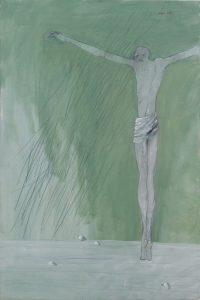

Ugo Untoro: Give Me a Cross, Ölfarbe und Kohle auf Leinwand, 150x100cm, 2008 (Photo Biasa Art Space)

Ugo Untoro: Cerita Pendek Sekali (Kurze Kurzgeschichten), Museum dan Tanah Liat, Bantul, Yogyakarta 2006

© Ugo Untoro, 2006-2008 © Biasa Art Space, 2008 (Photo) © Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-6. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter