The Middle East is one of the most important geo-strategic regions in the world. This is due to its geographical position, its richness in oil and gas but also due the nature of the conflicts that are taking place in this region and that have a deep impact on a very big number of people even outside this region. It is therefore reasonable and even important to have an understanding of what is going on in this region that is again very much in the media focus after the Arab Spring and several armed internal conflicts.

What surprised me most when I started to live in the Middle East for several years was that the reality I was facing there is so much more complex and interesting than what an average informed citizen of a western country would expect if he would only follow the media reports in his or her home country. There is a comparatively small number of journalists or political analysts in the West that have the knowledge, the access to media and the ability to explain the complexities of life and politics in the Middle East to the public in their countries in a way that is free of a patronizing attitude and also unbiased regarding the “official” narrative that is always dividing the world neatly into the “good” and the “bad” one’s, i.e. those that are considered worthy to be supplied with the most modern military technology and those who are on the receiving end of this annihilation machinery. The reality is unfortunately more complicated than this Manichean world view suggests: there are no “good” one’s – it’s frequently just about which of the groups involved in a conflict is serving our interests better. Nothing personal, it’s all just about oil, gas and political influence.

In order not to leave the field exclusively to those “experts” who still perpetuate the Orientalist perspective about which Edward Said was writing long and controversial books, it would help already a lot if we would perceive the Middle East as a region where people live that are not really different from us. And what would be easier than to perceive them in the way they are expressing themselves, for example by art, literature, cinema and all other kind of cultural activities. There is a thriving cultural industry in all these countries and since I am dealing here in this blog mainly with literature, I just want to point at the fact that there is an extremely interesting contemporary Arabic literature that is to a growing part available in other languages (some of it is even written in English or French).

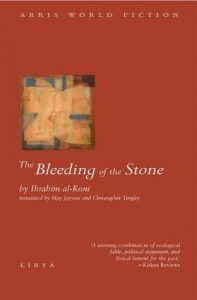

In my last blog I wrote up on an interesting novel by Ibrahim al-Koni. I am absolutely convinced that reading his books or the excellent books of Hisham Matar (he writes in English) can give a reader a much better understanding of what’s going on in Libya nowadays. The same is true for the writings of Algerian writers like Boualem Sansal or Yasmina Khadra. The Palestinian/Israeli conflict is presented in western media usually in a very partial and biased way. Those who read Ghassan Khanafani’s stories or the poetic books of Mahmoud Darwish, one of the greatest poets of our times will understand that there is also another side of the story. Readers of Alaa al-Aswany’s “Yacoubian Building” or Edwar al-Kharrat’s novels will have a deeper understanding of the problems of the Egyptian society.

And these are just a few examples. I am not saying that reading novels, stories and poems can replace the serious study of history, political science and other relevant subjects. But great literature can give you an insight in a culture that goes indeed very deep and sometimes much beyond rather dry textbooks. And beside from that it is just sheer pleasure to discover great works like the “Cairo Trilogy” by Naguib Mahfouz, the “Diary of a Country Prosecutor” by Tawfik al-Hakim, the autobiography of Taha Hussein, or the dark masterpieces of Abdurrahman Munif, especially his “Cities of Salt”.

Those who want to have a short overview about Arabic literature have now an excellent opportunity to discover this interesting literary continent. David Tresilian’s “A Brief Introduction to Modern Arabic Literature” gives on less than 200 pages a very reader-friendly overview on the history of Arabic literature. In several chronological chapters we learn about the main epochs in modern Arabic literature and are presented the main writers with a very short presentation of their major works.

Tresilian also pays special attention to poetry, the problems of the diaspora, and the development of a publishing industry in a surrounding where authors and publishers are always threatened by censorship or even worse (many Arab authors have been in prison at least once or have been threatened in one way or another for expressing themselves in their books). Book distribution is also a challenge that is hampering the outreach of contemporary Arabic literature in the Middle East, especially outside the capitals. On the other hand, publishing houses in Beirut (the main publishing place in the Middle East) and Cairo seem to thrive and there are a growing number of book fairs and bookstores that attract a growing number of readers. After the Nobel prize was awarded to Naguib Mahfouz, there has been also a (modest) translation boom in the English and German speaking countries at least.

Unfortunately the book is not covering the Maghreb region, although some of the most important Arabic authors origin from there. Literature that is written in other languages than Arabic is equally not considered, even when the authors come from the region. (That excludes for example the excellent novel “Beer in the Snooker Club”, by Waguih Ghali) These limitations were obviously necessary in order not to exceed the size of a “Brief Introduction”. Within these limitations the book is highly recommended to those who wish to discover one of the most interesting literary “continents”.

David Tresilian: A Brief Introduction to Modern Arabic Literature, Saqi, London San Francisco Beirut 2008

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter