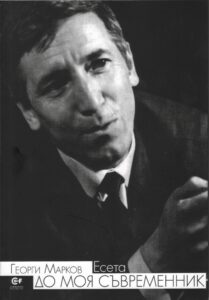

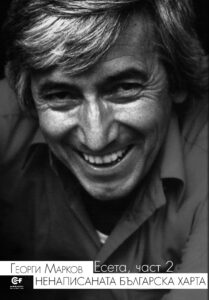

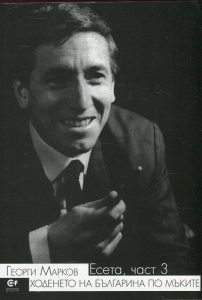

I am reading right now (in Bulgarian) a three-volume edition of the essays of the Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov, who is for me one of the most remarkable Eastern European intellectuals of the time between the end of WWII and the Fall of the Berlin Wall. Unfortunately he is in the West mainly known for the fact that he was assassinated in a rather bizarre way by a hit-man in the service of the Bulgarian State Security, and not for his work and the brilliant analysis of the Bulgarian and other regimes in Eastern Europe.

The edition contains many essays that are – according to the information in the books – published here for the first time in print, and it is remarkable how fresh and highly relevant these essays that are at least four decades old, are today. A fact that says also something very unpleasant about the situation in Bulgaria – still very much run by the networks of people with links to the former Bulgarian State Security and their underlings – and most other Eastern European countries.

The publisher, who brought recently among others also Varlam Shalamov, Yevgenia Ginzburg, and works of Alexander Solzhenitsyn to the Bulgarian readers, has to be praised for this deed.

However, I have also to mention that the footnotes are to me very annoying. While some of them are ridiculously inadequate – is it really necessary to try to explain in two lines who Thomas Mann or Pablo Picasso were, and does the fact that the publisher added these footnotes mean that this edition is intended for an audience that is missing even an elementary Bildung? -, others are inaccurate, and even manipulative.

One example: Pablo Neruda is described in a footnote as an author that was “occupied by communist ideas”, which is clearly a strong understatement; he was in reality a Stalinist hardliner and active GPU/NKWD agent with blood on his hands; he played a big role in the Trotsky assassination, and allegedly some others, and he personally took care of deleting non-Stalinist leftists from the list of people that would be granted a place on a rescue ship and visa to Chile, people desperately trying to leave unoccupied France in 1940; Neruda knew perfectly well that his selection (I am almost tempted to write Selektion here) was in fact a death sentence for almost all of them, executed either by the Nazis, or by the assassination squads of Stalin (Victor Serge has written in detail about such murderous “intellectuals” as Neruda). The footnote about Neruda is in this context extremely misleading.

Another example is Günter Grass, who according to the footnote was a “far-left” writer. For those who don’t know it, Grass was a life-long supporter of the German Social Democrats, even when he left the party for few years out of disappointment; he wrote speeches for his close friend, Chancellor Willy Brandt, one of the most fervent German anti-Communists, and he was himself a lifelong anti-Communist. The German Social Democrats, and also Grass himself, were never “far-left”, and the footnote is either reflecting a completely uninformed editor, or is – what I don’t hope, but cannot completely dismiss as a possibility – intentionally manipulative, “far-left” being in Bulgaria a common epithet for a Communist sympathiser.

On the other hand, it is mentioned that Salvador Dali left Spain after the Civil War, but “refrained from political activities”; those who don’t know who Dali really was, might get the impression that he was an active anti-fascist who left the country to avoid persecution – while the truth is exactly the opposite: he showed a servile attitude towards the dictator Franco and open sympathies for fascism, and he had even the bad taste to (figuratively speaking) spit on the grave of his former best friend Garcia Lorca, who was murdered by Dali’s new friends. There was a reason why Max Ernst crossed the street when he got sight of Dali during his emigration, and it was not only for artistic reasons that he didn’t want to face his shameless plagiarist!

Unfortunately, all intellectuals with sympathies for the (democratic) left seem to be described in a way similar to Grass, while in cases of intellectuals or artists with fascist sympathies a sudden amnesia seems to have taken hold of the editors.

But not only when it comes to Western artists and intellectuals, this edition goes astray; almost all Bulgarian authors – most of them household names for the readers of this edition; even the famous Blaga Dimitrova has her two-line resume – have a footnote; only Lyubomir Levchev, a key figure of Bulgarian literary life in the time of Communism is not worthy(?) of a footnote. This gifted poet, a close friend of Markov while the later dissident was still living in Bulgaria, who made a career as an orthodox Communist literary functionary, played for example a very active role in the persecution and partly expulsion of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria in the 1980’s (euphemistically called “Revival process” by the Communists), a role in which he seems to take pride until today.

I doubt very much that the missing footnote for Lyubomir Levchev was an editorial oversight (I have privately my suspicion for which reason the footnote is missing), and this missing footnote, together with the other inadequate, wrong, and manipulative footnotes decrease my pleasure in this otherwise great and valuable edition very much. I hope that this edition will see many reprints, and that many especially young Bulgarians will read it – but with more appropriate and correct footnotes!

Георги Марков: До моя съвременник; Ненаписаната българска харта; Ходенето на българина по мъките (3 volumes), Communitas Foundation, Sofia 2015-2016

My remarks are mainly based on the first of the three volumes, which I have finished so far.

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014-7. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter