One of the tangible results of my summer holiday in Turkey was a big stack of books I bought in various Istanbul bookstores. Some of these books have been already reviewed here during the last weeks, including a (for me) surprisingly good crime novel.

Today I will review another book from my Turkish book pile, the novel The Devil Within by Sabahattin Ali. The book is translated in French and in German, but unfortunately (as it is so frequently the case with good books written in other languages!) not in English – although this novel is considered one of the most important books of modern Turkish literature.

Only 4% of the new books published on the British and American market are translations I read recently – and without some non-profit or non-mainstream publishers it would be even worse ! I am sure readers in these countries are as curious as people in other parts of the world – so why are most publishers failing their costumers so badly? Maybe I should write a bit about this phenomenon and its consequences (together with the fact that native English speakers frequently know no foreign language). But I digress.

The Devil Within is a partly autobiographical novel that was first published in 1940. It is the story of Ömer, a young man from the Western Anatolian province that lives now in Istanbul. He has an uninteresting job at the post office, but he rarely shows up. He got this position through an influential relative and the pittance he earns as a salary requires his presence in the office only rarely.

With much more pleasure is Ömer hanging out with his (former) student colleagues, talking about literature, politics, philosophy – and about Ömer’s theory of the Devil Inside. He is convinced that each person has a demon inside that interferes in the lives of people and prevents them from achieving their aims and real happiness. But as a reader we have the feeling that this is not serious philosophy, just vain talk of some young guys who take their talks in the various meyhane – usually paid by some journalist or writer who like to play the philanthropist and to have a crowd of devoted fans around when they make acerbic remarks about their colleagues and competitors – for something serious and erudite. The Devil Within is a novel mainly about Istanbul intellectuals in the late 1930s.

In the opening chapter, the author takes us on one of the many ferry boats that are until today such a common means of transport in Istanbul. Ömer and his friend Nihat have a discussion about their favorite topics when Ömer is spotting a girl sitting nearby to which he feels immediately attracted. By lucky circumstances, he can make the acquaintance of Macide, who is as it turns out, a distant relative. Macide is living with Aunt Emine and Uncle Garip, an impoverished couple and turns out to be a very gifted musician and a very modern and independently thinking girl.

I don’t want to give too much away of the story, but I liked Sabahattin Ali’s craftsmanship. The novel is well composed, the love story between Ömer and Macide is unfolding rather fast but convincingly. Also the other characters of the book are well developed and have depth. Most of the characters are intellectuals, a kind of elite of the Istanbul circle of writers and journalists, but Mecide (and with her probably also the reader) is not very much impressed. Her sharp intellect realizes that most people in Ömer’s circle are good mainly in three things: talking, drinking, and badmouthing their more talented colleagues. A splinter group of these intellectuals, among them Ömer’s friend Nihat and the shady Professor Hikmet dream of a vague dictatorship in the spirit of the fascist “Pan-Turanism”.

Money plays an extremely important role in this milieu – Ömer and his friends are desperately short of funds all the time. Nihat talks Ömer finally into committing a criminal and ethically disdainful act: he is blackmailing a colleague who was always very friendly to him but who “lent” some money from the cassa in a situation where he saw no other way out of a difficult family situation.

Macide, probably the most interesting character in the novel, is going through a learning process. She becomes more and more disappointed, and when Bedri, the music teacher who years ago recognized her talent as a musician, and who happens to be a long term friend of Ömer, is meeting her and Ömer, she starts to understand what she is missing in her relationship with Ömer.

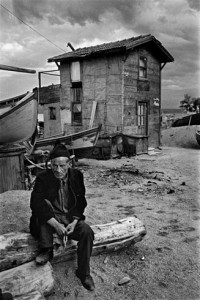

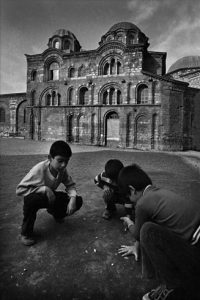

The book is interesting for various reasons. The novel was a still quite new genre in Turkey when the book appeared in print. But Ali proved in his three novels to be already a master in this craft. Also the subject matter is very interesting. The book shows a generation of young intellectuals who live without a real perspective. The things they learned in university (and the Turkish universities at that time were excellent) or abroad (Ali for example had studied in Germany) prove to be useless. Despite the reforms of the founding father of modern Turkey, the old mindsets of the society were still intact, positions were distributed not according to the qualification a person had, but as a result of nepotism or even open corruption.

Macide and Bedri are rays of hope in this rather bleak picture of the Istanbul of the late 1930s. A modern, self-confident woman, and a loyal and supportive partner who shares her values and interests – that’s almost too good to be true. But I enjoyed the fact that the alleged Devil Within that is frequently just an excuse for personal weakness and laziness seems not to triumph in the end.

Sabahattin Ali was (probably) born in 1907 in Ardino (Bulgaria) and was murdered in 1948 under unclear circumstances near the Turkish-Bulgarian border. There is evidence that the author was killed by the Turkish Secret Police before he could cross the border to Bulgaria. In the last years of his life, Ali had permanent problems with censorship, arsonist attacks on the office of his journal, and he had to serve several prison sentences for his writings. Today he is considered a modern classic – and rightfully so.

Sabahattin Ali: İçimizdeki Şeytan, 1940; Le Diable Qui Est En Nous, Le Serpent á Plumes, 2008; Der Dämon in uns, Unionsverlag, Zürich 2007

© Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com, 2014. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and mytwostotinki.com with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter