As a rule, we learn very little from writers about their failed writing projects. Which author is willing to admit that a considerable part of the writing efforts were unsuccessful and that these efforts did not progress beyond a more or less extensive experimental stage. Occasionally such a failed project is mentioned – often in a anecdotal, humorous way – by successful writers, but generally only in the form that aims to portray the author as a hard-working person who usually (but not always) manages it to publish something presentable. However, in cases where an author’s entire legacy is available for literary research, one can often get a different impression, and creative failure seems to be more the norm than success, at least for authors who place high qualitative demands on themselves.

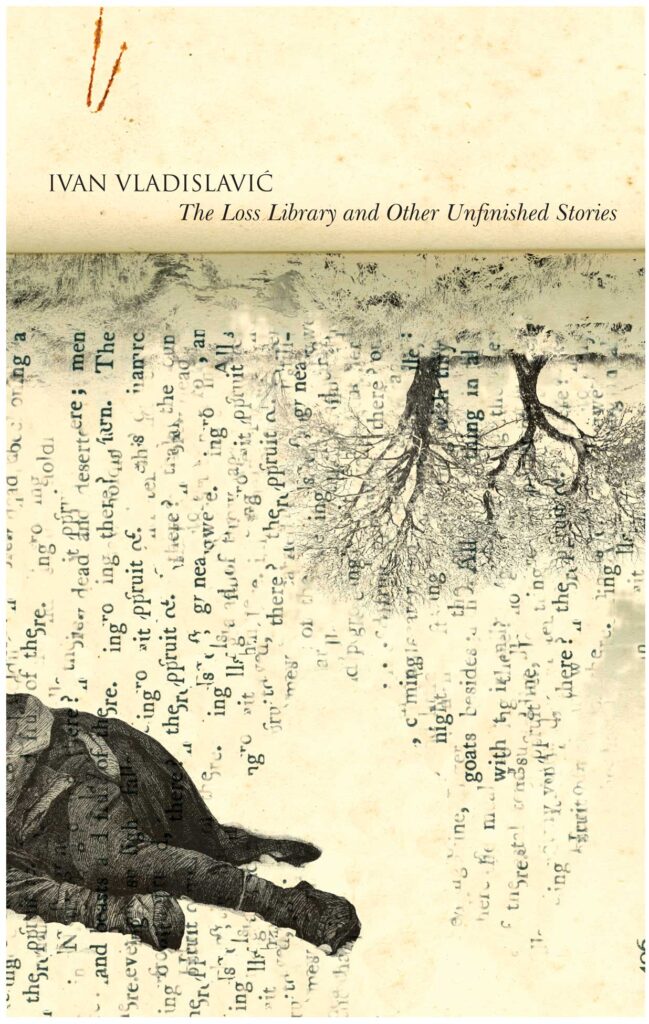

The volume The Loss Library and Other Unfinished Stories by the South African author Ivan Vladislavić is one of the not very many books in which a contemporary author gives the reader an insight into his writing workshop and failed attempts at storytelling. From his notebooks he made a selection of twelve (actually thirteen) ideas for stories that did not progress beyond the embryonic stage and could not be completed as intended.

Personally, I think this book of failure is extremely successful – a beautiful paradox! And by openly analyzing what these narrative ideas are all about, where they may have come from and why they ultimately failed, the author creates something new and unexpected: a collection of hybrid texts that lie somewhere on the border between narrative , essay and occasional autobiographical vignettes. Vladislavić talks about his literary influences and so, quite casually, a kind of literary genealogy emerges, and it is obviously no coincidence that this genealogy contains authors who made digression and failure, fragmentary and hybrid storytelling a principle to which they have committed themselves in their own writing. And in this neighborhood of Robert Walser and Borges, Sterne and Perec, DeLillo and Rabelais, Sebald and Calvino, Vladislavić has carved out his own niche with this small, very interesting book.

The texts in the book are on average eight to ten pages long and this concentration on the short form prevents the reader from having to suffer through long essayistic passages. Geographically and timewise, the texts cover a wide range – from Belgrade during the Second World War to Komodo and New York on September 11th – and the volume also covers stylistically a wide range. The title story, The Loss Library, can even be read as a completely well-executed story, although it is about the many unwritten books by famous authors. Since I have recently read some theoretical works on photography (Barthes, Sontag, Berger, Bonnefoy), the texts where a photo was the trigger for writing, such as in the text about Robert Walser and the other photo showing dead men – executed by the Nazis during WWII in Belgrade – that had kept their hats on, were particularly interesting to me. In the end, this overlay meant that the originally planned Walser story remained unfinished.

I found myself entertained in a very intelligent way while reading this book. Now I would like to read more from this obviously very interesting author. Another discovery that I owe to the Indian publisher Seagull Books, who included in this volume beautiful illustrations by Sunandini Banerjee, who has already illustrated books by Yves Bonnefoy and Thomas Bernhard.

Ivan Vladislavić: The Loss Library and Other Unfinished Stories, Seagull Books, Kolkata 2012

© Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki, 2014-24. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Thomas Hübner and Mytwostotinki with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Facebook

Facebook RSS

RSS Twitter

Twitter